A Communal Model of Care from Ottoman Times: A Research Project, Art Exhibit and Webinar Series

The covid-19 pandemic has made us feel, like never before in our lifetimes, the tension between personal and collective health: to save the group, we must isolate ourselves. Yet, looking back at a centuries-old hospital model in Istanbul, community was essential to ensuring both the health of the individual and the collective.

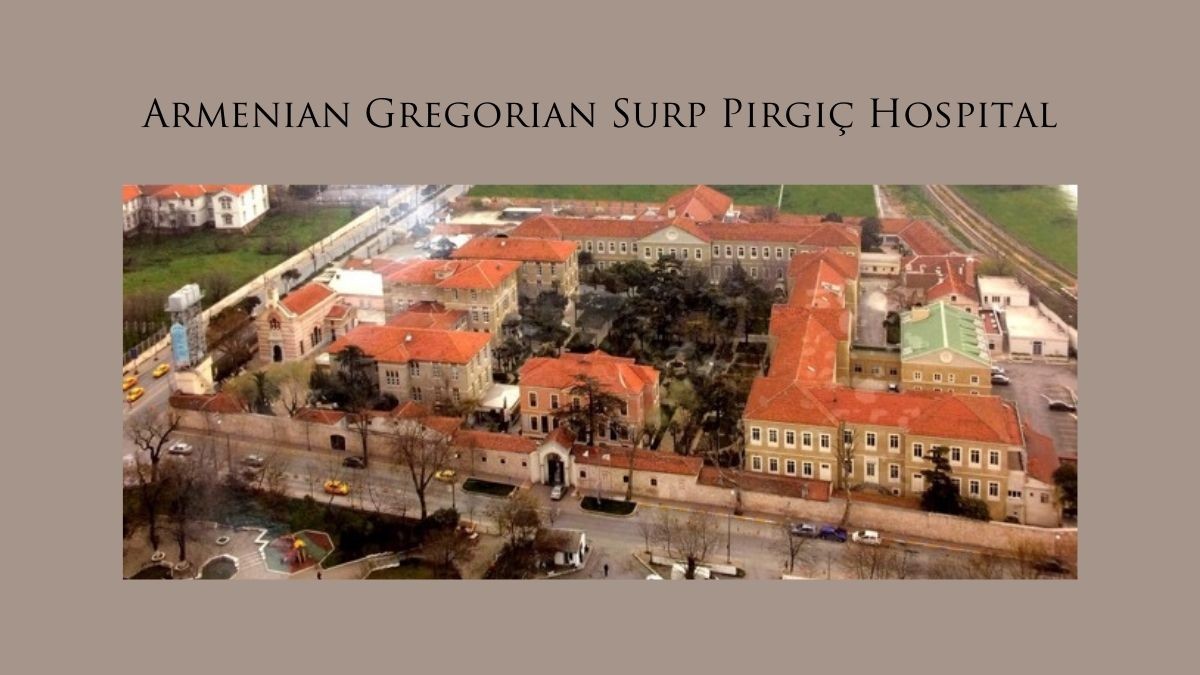

I spent the first year of the pandemic researching this hospital model with Gabriel Doyle, a historian who wrote his dissertation on 19th-century practices of care in Istanbul, and Cemre Gürbüz, an architect and urban researcher in the city. We limited our study to five of the oldest hospitals, which were each founded by and for their own religious communities during periods of epidemic breakout: the Greek Orthodox Balıklı Rum Hospital (1753), the Armenian Gregorian Surp Pırgiç Hospital (1834), the Armenian Catholic Surp Agop Hospital (1836), the Jewish Or-Ahayim Hospital (1898) and the Bulgarian Orthodox Evlogi Giorgiev Hospital (1902).

We sorted through sparse and scattered archival sources and conducted interviews to uncover the stories of the people who most intimately knew these hospitals, and yet who have left fewer traces in the city’s official medical history: nurses, volunteers, patients, neighbors, workers and visitors. By telling the story of these hospitals through their eyes, we aimed to share a bottom-up understanding of health and to paint a complex picture of a form of care that is inherently communal. We called the project ‘Our Hospital’ (‘Bizim Hastane’), which is how people we spoke to often referred to these hospitals.

The pandemic made our job more challenging, since the hospitals are closed to researchers, and since those who remembered their earlier forms are classified at-risk. Moreover, only one of the five hospitals keeps an institutional archive, and the sources we found are in six different languages. What we did find, though, confirmed that these hospitals had once been a place of communal activity. We learned about groups like the Blue and Pink Angels, volunteer women who tended to and entertained elderly patients; and the soccer teams of hospital staff and priests who scrimmaged in a field next to the Bulgarian Hospital. We also learned about how these hospitals were both havens and targets during moments of ethnic violence and war; about how they gave jobs to people left out of a changing urban economy; and about how they were used as diplomatic tools, since their boards often stood in as official representatives of the community.

Near the beginning of our research, we spoke with the art space Karşı Sanat about curating an exhibit on the topic. The curator Melis Bektaş invited 17 artists to interpret various themes that these hospitals evoked, including the place of the body in the city, social distance and proximity, and the way that women and marginalized groups are treated by the medical community. The exhibit ‘Finding a Cure in Istanbul’ ran last summer in the Yaklaşım Tünel, an evacuation tunnel for a major metro line that the Istanbul municipality and Istanbul Metro opened for the first time as a permanent exhibition space. In it, we displayed photos from the five hospitals that had the feel of a family album, projected a video (produced with Ozan Çağlar) that juxtaposed interview excerpts and shots of the hospitals today, and hung boards with words in various languages that stretched our vocabulary on the hospital, and below them, direct quotes about the five hospitals that brought these concepts to life.

Before the opening of the exhibition, we spoke with Columbia Global Centers | Istanbul to organize a webinar series to delve deeper into questions that our work had provoked. We wanted to open up the discussion to people in Istanbul and abroad, and Merve Ispahani and Seden Gürlek of the Istanbul Center were particularly interested in how we used both research and the arts to explore pandemic-related issues. We decided on an interdisciplinary program that tapped into the Columbia network both in Turkey and around the world, with one talk in Turkish and one in English, dissecting the hospital from a non-medical perspective. Our driving question was how radical urban transformation and the fall of an empire have impacted practices of care in Istanbul, and how trends in this diverse city can illuminate developments in public health on a global scale. The series, titled ‘Heritage of Healing,’ ran on June 30 and August 5.

For our first webinar, Şehirde İyileşmek (Healing in the City), we invited Murat Güney ‘16GSAS, a sociologist and coordinator with Vizyon2050 of the Istanbul Planning Agency, to moderate a talk with medical historian Fatih Artvinli and documentary and experimental filmmaker Deniz Tortum. Fatih gave a historical and geographical overview of health institutions in Istanbul and touched on what place these five communal hospitals — and others that preceded the “city hospital” model that we know today — occupied in the city. Deniz shared his impressions of the exhibit, drawing parallels between the sensorial experience of walking through the tunnel and the experiences of crossing a hospital corridor, entering the tubings of a body and living in a sick city. The speakers then discussed how people now (and in the future) may access care differently because of developments in technology, in a profit-based industry and in large-scale urban planning.

The second webinar, Rethinking Health and the City, was moderated by medical anthropologist Christopher Dole and featured architectural historian Burçak Özlüdil Altın and cultural anthropologist Ayşecan Terzioğlu. Burçak reminded us that imperial hospitals in the late Ottoman Empire were marginal health institutions to make the point that concepts like health and the hospital change over time and space. Ayşecan showed how social inequalities were made apparent as political actors debated how to provide healthcare during epidemics in Turkey over the past century. Christopher concluded by saying that while the modernizing Turkish nation “exiled” healers from the secular medical landscape, these traditional practices are still embedded in society because their interrelational vision of health, and of living, continues to be relevant.

We were moved by the contributions of both the artists in the exhibit and the participants in the webinar series, and of course by the people who shared their own memories and archives of the five hospitals with us. We will continue to collect these stories; if you have questions about our project or would like to send us your own ideas, please contact us at [email protected]