100 Years of Despair

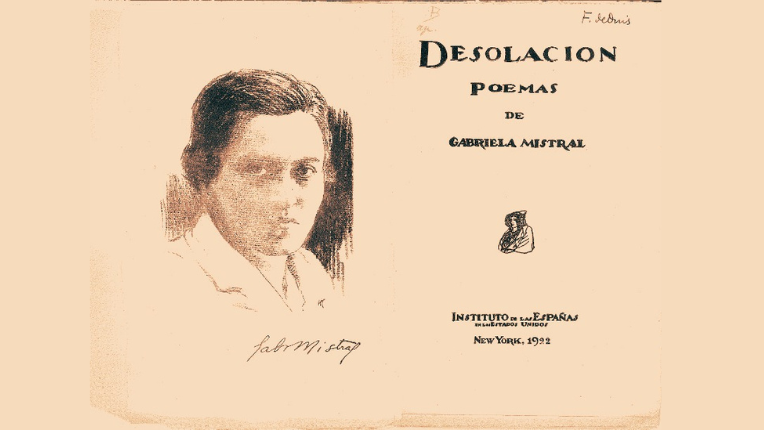

The story of how 100 years ago, Gabriela Mistral's first book, "Desolación," was published by Columbia's Instituto de las Españas.

The following is the story of how a a primary school teacher from rural Chile became a world-renowned poetess and Nobel laureate, and how the life of this modest woman who shied away from the spotlight and disliked public attention, was forever imprinted by her unexpected, lasting relationship with Columbia and, in consequence, with the city of New York. It was in New York where Gabriela Mistral was first published, it was there where she taught, where she lived, where she loved, and where she died.

But this was highly unlikely to have happened had it not been for a young Spanish Literature professor named Federico de Onís. After noticing the greatness of Godoy’s early works, and perceiving her deepness and complex nature, he made her an offer that would set the rest of her life in motion, propelling this unassuming intellectual into the global spotlight.

Early Life and First Writings

Lucila Godoy was born in 1889 in the town of Vicuña, located in the Elqui Valley of northern Chile, but was raised in the small nearby village of Montegrande. Her father, a teacher, abandoned the family when she was only three and left her to be raised by her mother Petronila and her older sister, Emelina, who taught primary school and was Lucila's first instructor. In spite of the strained relationship with her father, he was a big influence in Godoy's life. While she was still a young girl, she found several of his poems while looking at his old papers: “I found some very beautiful verses of his that impressed my childish soul in a very vivid way. Those verses of my father, the first ones I read, awakened my poetic passion,” she would write years later.

In 1904, Godoy relocated to the nearby city of La Serena, where she started working as a teacher’s assistant and began collaborating with El Coquimbo and La Voz del Elqui, two secular, liberal newspapers affiliated with the Radical Party, which since its foundation in the 1860s, had cultivated social-liberal and secular ideas and was closely related with Freemasonry. This collaboration allowed her to befriend El Coquimbo's founder, Bernardo Ossandón, who would have a profound influence in her life. Ossandón gave Godoy access to use his personal library, where she could read from his collection as well as develop her writing skills. “One day an old journalist found me, and I found him. His name was Bernardo Ossandón, and he had a large and excellent library, which was very rare to have in a province [outside of the capital city of Santiago]. I still fail to understand how this good sir opened his treasure to me,” she would say.

Befriending Ossandón – a Radical and Freemason – was determinant in Godoy’s thinking and a contribution for her development both as an educator and a writer. Through his library she could access secular, liberal books that shaped her vision of the world. She would later turn these thoughts into prose, covering a wide range of topics, including gender equality, education, religion, and the American continent, among many others. It was there where she discovered classics from Latin America and the rest of the world, and where she first read French writers Michel de Montaigne and Frédéric Mistral, who would inspire the pen name by which she would become famous worldwide.

Though she was barely 15 when her works started to be published, even the earliest of her writings reveal her strong advocacy for women’s education: “The educated woman stops being a helpless being,” “To instruct a woman is to make her worthy and lift her up,” “Instruct women; there is nothing in them that should position them in a lower place than that of men.” They also evidence her critical views on religion, specifically of its role in the education of youth: “I would show them the sky of astronomists, not the one of theologists.”

But her progressive ideas led her to trouble. In 1905 she was supposed to start formal training as a primary school teacher at an Escuela Normal in the northern city of La Serena, but she was denied entrance based on her controversial writings; she was considered a revolutionary socialist with pagan ideals unfit to teach young people. Though her prose might have been controversial, she considered herself a Christian, who spoke to God regularly, albeit with a very personal conception of religion.

The Birth of Gabriela Mistral

Until 1908 Godoy signed her publishings with several modified versions of her real name. The first time she used the pen name of Gabriela Mistral was in 1908, under a poem entitled “Rimas” (Rhymes).In 1909 she was left heartbroken after her first love, Romelio Ureta, committed suicide, a topic that would be consistently present in her writings during the next few years.

In 1910 Mistral validated her skills at Escuela Normal N°1 in Santiago and was granted the degree of Profesora de Estado (State Teacher) which authorized her to teach secondary students. In the next years she would move around Chile teaching in various cities. While living in Los Andes in 1914, she got news that the Chilean Society of Writers had organized a literary contest entitled Juegos Florales (Floral Games). She submitted three poems under the name of “Sonetos de la Muerte” (Sonnets of Death), which spoke of her grief following the death of Ureta. In mid-December that year, she was announced winner of the event, though she was a complete unknown both to the public and the jury. The award ceremony was held in Santiago on December 22 and was attended by Chilean President Ramón Barros Luco and the first lady. But Mistral was too shy to come forward and receive her award, choosing instead to hide in the gallery and quietly watch as someone else read her sonnets out loud:

From that frozen niche the men have put you,

I will lower you down to the humble, sunny earth.

That I have to sleep there, the men do not know,

and that we must dream on the same pillow.

Even though she was not publicly recognized, winning the Floral Games secured Mistral a spot in the Chilean literary scene. At the same time, she had taken incipient first steps towards internationalization. In 1912, she wrote to the Nicaraguan poet and writer Rubén Darío, who at the time lived in Paris, where he directed two magazines: Elegancias and Mundial. In response, Darío energetically encouraged her to make her writings public, and thus, in 1913 “La Defensa de la Belleza” (The Defense of Beauty) became her first story published outside of Chile.

While she was still working as a Spanish teacher in Los Andes, Mistral met and befriended Pedro Aguirre Cerda, a member of the Radical Party who would later become Minister of Education and subsequently President of Chile. In 1918, Aguirre Cerda appointed Mistral as director of the all-girls Liceo Sara Braun in the southern city of Punta Arenas. Two years later she was relocated to the city of Temuco to direct its Liceo de Niñas. In 1921 she arrived in Santiago, where she was named director of the Liceo N°6, a new school for girls. Since Mistral had not attended Universidad de Chile’s Instituto Pedagógico – where secondary school teachers where trained – her appointment created tension with other female educators, who publicly accused her of being favored by Aguirre Cerda. According to Mistral’s letters to friends, the leaders of the smear campaign against her included the National Teachers Association and Amanda Labarca, a graduate of Columbia’s Teachers College, renowned teacher and one of the main figures of the female emancipation movement in Chile: “They tolerated my appointment as director of the liceos while I lived in the provinces, but not in Santiago. My guild will never forgive me for not having a professional degree. Aguirre Cerda is the sole protector of my career. He knows that, in order to justify my appointment, they even said that I was his mistress. Add to this campaign Mrs. A. L. H. [Amanda Labarca Hubertson], a woman who fans herself with her authority and the power of her insidiousness.”

As she acknowledged in a 1922 letter to her friend and writer Eduardo Barrios, Mistral was disappointed that her 18-year career in education was being questioned because of her lack of formal training. “I am disgusted by my guild in Chile,” she stated, unsure of what her next moves should be. Although her love for teaching was profound, in the early 1920s she was considering early retirement, but was apprehensive over her financial stability, as she was responsible for supporting her mother.

Federico de Onís and “Desolación”

Born in Spain in 1885, Federico de Onís was the son of the main librarian of Universidad de Salamanca. As a child he often interacted with his father’s acquaintances, such as the famed novelist and essayist Miguel de Unamuno, under whom he would later study at Universidad de Salamanca, and eventually befriend. After receiving his PhD in Literature, at 26 he attained a professorship at Universidad de Oviedo, but four years later, in 1915, he moved back to Salamanca to teach Spanish Literature at his alma mater. A long promising career awaited him there, but in 1916 he was contacted by Nicholas Butler, President of Columbia University, who invited him to join the faculty and establish a program of advanced studies in Spanish.

At 30 years old, de Onís got established in New York, where he took part in the founding of Columbia’s Department of Spanish (currently the Department of Latin American and Iberian Cultures). His appointment was pivotal for the future development of Hispanic studies at the University: for 40 years, de Onís strove to disseminate knowledge on Iberia and Latin America and promote Hispanic culture across the US. In 1920 he created the Instituto de las Españas (today’s Hispanic Institute); in 1930 he founded Casa Hispánica, where he organized concerts and lectures, and in 1934 he created Revista Hispánica Moderna, an ongoing academic journal focusing on Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian topics.

Five years after his arrival at Columbia, on a January night in 1921, during a lecture at the Hispanic Institute, de Onís read aloud poems written by an unknown school teacher from a rural town in Chile who published poems under the pen name of Gabriela Mistral, who he knew because a few of her writings had been published in Spanish newspapers. The over 400 students and faculty present that evening responded to the originality and moral force of the woman's writings. According to de Onís, “The audience was mostly made up of teachers, and they were immediately enthusiastic. Here was one of their own, a teacher, who was also a fine poet. They wanted to know where they could get her poems and all I could give them was a handful of clippings.”

After that 1921 lecture, de Onís wrote Gabriela Mistral what would be the first of dozens of letters over several decades. In representation of the Spanish teachers of the United States, he asked permission to publish her work in an anthology. At the beginning the poetess reacted in her common shy and reserved nature; she had received previous offers to publish her work but had, until then, been too modest to accept. However, eventually de Onís got her approval. She agreed to gather her writings, which by then were mostly scattered, and send them to New York.

In a March 1922 letter, de Onís informed Mistral that as soon as the manuscripts arrived in New York, he shared the information with the more than 300 Spanish teachers living in the city, as well as with the authorities of the Instituto de las Españas, who were delighted to hear the news. He assured her that in editing the book he would ensure that all of her instructions were followed. De Onís also commented that the Hispanic Institute would cover the publishing costs of the book and assured her that her royalties “would be the highest possible, with no doubt higher than what any publishing house would pay.”

Later that year, Mistral’s first book, a collection of poems entitled “Desolación” (Desolation or Despair) was published by Columbia's Instituto de las Españas. The author dedicated her first official publication to Pedro Aguirre Cerda and his wife, Juana de Aguirre. A few months after the release of the book, Mistral and de Onís met for the first time in person, at the end of 1922 in Mexico. After retiring from her job as a teacher, Mistral had moved there to assist the Minister of Education José Vasconcelos, in the reformation of the primary school system, while de Onís was in the country offering Spanish Literature courses and conferences.

Though there are no records of Mistral and de Onis’ encounter in Mexico, six months after, she wrote him letting him know that, back in Chile, she had seen a copy of “Desolación” for sale at a bookstore, and that she was very pleased with how the book had turned out: “it’s sober, serious, and beautiful. I would not have done it differently.” She also had words of gratitude towards the Spanish professor, for the preface he had written: “Your opening words are so kind and generous that I don't know how to thank you for them. They seem like the presentation of a true author. There is much tenderness in them and I, who appreciate affections above all admiration, have read them with religious emotion.”

The volume was divided into five sections: Life, School, Children's Stories, Pain, and Nature, and as the author herself confessed in the very last poem, entitled “Vow,” the book is a testimony of Mistral’s aches and misfortunes: “In these hundred poems lies bleeding a painful past, in which the song got bloodied to relieve me.”

From the moment it was published, “Desolación” was a critical success. For Julio Saavedra, literary critic, professor, and Mistral expert, the volume is much more than a book of verses: “Its lyricism is rooted in a lived tragedy and the feelings that arise from it.” According to him, the poetess possessed a deep inner world, in which “fantasy, physical and spiritual sensitivity is made one with the ever-pulsating emotion of living amidst a sacred and inexplicable mystery.” In 1954, fellow Chilean poet Pablo Neruda wrote that the publishing of “Desolación” opened the door to an unparalleled poetic emotion around the American continent. The book contained the “Sonetos de la Muerte,” which according to Neruda had such torrential force that they opened the heartbreaking intimate core of its author. “Its introductory stanzas advance like volcanic lava,” he wrote. In his 1991 biography of Mistral, Chilean writer Volodia Teitelmboim remembers that “Desolación” was a fundamental part of his primary education. Born in 1916, Teitelboim recalls having to memorize several poems, such as “Shame,” “The Creed,” and “Plea.” He also claims that “Desolación is the capital book of 20th century Latin American poetry and one of the most singularly tragic.”

Even if de Onís and Mistral had only crossed paths for the publication of her first volume, this action would have sufficed to change the course of Hispanic American literature forever. In 1924 Mistral’s second volume, “Ternura” (Tenderness), was published in Spain. A year after, she joined the League of Nations to work in intellectual cooperation, consolidating her international career. Though she would occasionally return to Chile to visit, she never lived in the country again, remaining an expat for the rest of her life.

Read the complete chapter about Gabriela Mistral and her decades long relationship with Columbia in "Gabriela Mistral: Poetess in New York," the first chapter of the book “Columbia University and Chile: Over 100 Years of History” available here.