Discussion reveals the history of police brutality and corruption in Oakland

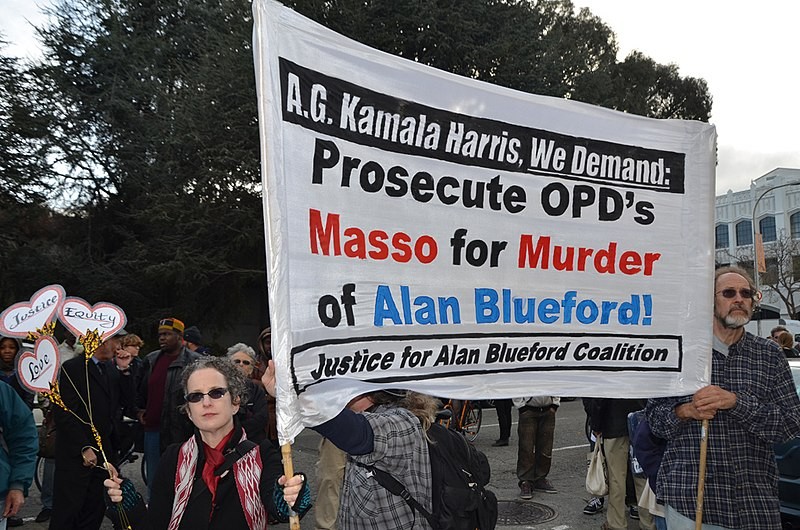

The book exposes the history of police brutality on Oakland, but it is a familiar and perhaps even universal story people can bear witness to in countless communities that stretch around the world.

The Istanbul Center hosted a discussion Jan. 19 with Ali Winston, one of the authors of The Riders Come Out at Night: Brutality, Corruption, and Cover-up in Oakland.

The Turkish-American Winston, who co-wrote the book with Darwin BondGraham, spoke via Zoom with Emre Kızılkaya, vice president of the International Press Institute, as part of the center's long-running series with the institute exploring media issues.

The culmination of more than two decades of fearless reporting, the book by the Polk Award-winning investigative duo traces the history of Oakland since its inception through the lens of the city’s police department, through the Palmer Raids, McCarthyism, and the Civil Rights struggle, the Black Panthers and crack eras, to Oakland’s present-day revival.

The book’s prologue begins with a conclusion: “American law enforcement is broken.”

Oakland, Winston told Kizikaya, “has been under a formal reform program now for the longest period of time of any police department [in the U.S.] – 20 years ago this month.”

The riders in the book title were a group of police officers who were popular in the department beginning in the 1990s for pursuing aggressive tactics on the streets of the city.

“They got arrests, they hit number targets, they hit the quotas, they cleaned up Corners they took people off the streets,” Winston said. “It's how they did it that's the real issue. They would oftentimes plant drugs on people, they would write up false charges, write up false confessions. They would beat people into submission.”

The conversation provided a comprehensive framework to understand the situation of the police force in the United States, and the way the force interacts with their respective communities in various cities. The discussion also touched upon Turkey in the way that the two countries deal with their respective inner-city problems. The conversation ended with a couple of words of advice to young reporters from Ali Winston.

Talking about the initial formation and development of Oakland, Winston emphasized that the city has always had a strong blue-collar tradition. However, Winston said, the city had a “very powerful Anglo-elite that got rich on gold mining, on selling stuff to gold miners, which obviously for California is kind of the creation myth of the state that people were drawn out west mostly during the gold rush of 1849.”

Because Oakland grew tremendously during the second world war, it was a center of the war industries like Los Angeles, Portland, and Seattle. For this reason, there was a huge migration of Black people from the south and the southeast to the west coast for the war industries, to the cities such as Los Angeles, San Diego, Portland, Oakland, San Francisco, and Seattle.

From this period on, the Black population was the majority. At this point, Winston asserted that the Anglo-elites wanted the African American population to be temporary and returned to the south. When that didn't happen, they set about basically creating redlining neighborhoods through real estate covenants restricting people from buying housing.

“They put the police department into play to ensure that the African-American population didn't escape from those ghettos,” Winston said.

In turn, this led to the most famous explosion in Oakland's history – the creation of the Black Panther party in 1966, which was founded explicitly on a message of community control over the police and armed resistance to police oppression.

Oakland holds a place of distinction in American history, Winston said, because it reflects what happened in many other places, all these other west coast cities that expanded during the war and received this huge influx of Black people, they also had similar dynamics with their law enforcement agencies.

Winston emphasized that the pushback to the over-policing began in Oakland, and in many ways, Oakland trends ahead of history in the United States with regard to law enforcement and relations between community and police.

Kızılkaya moved the conversation to the book’s specific subject matter, namely the group of officers using of disproportionate force against suspects, false confessions, exonerating police officers, planting drugs and weapons on suspects and crime scenes, playing informants with drugs and dirty money. After providing an intriguing background to Kızılkaya’s questions, Winston provided another engrossing overview of the city during the 80s and the 90s.

Winston especially focused on the way high unemployment came in, the industry went away, and the narcotics trade became dominant in the area. Especially after crack cocaine hit the US, there was a substantial increase in violence and the same thing happened in Oakland.

With an even harsher change of policy in the late 90s in the city, Winston said that there was a lot of enforcement of low-level crimes, the idea supposedly being “to take the corners back from drug dealers and addicts.” From this point on, the conversation focused more on the said officers that give their nickname to the book’s title: “The Riders.”

Winston asserted that although these people were very brutal officers, they were not exceptional at all. As told in the book, “Their conduct was well known in the department and there were also quite a number of other officers in West Oakland who tag along with them on certain shifts and knew their conduct.”

Emre Kızılkaya then steered the conversation towards the whistleblowers in the book, asking about the reasons they were penalized and about the failed attempts to reform the department. Citing critical examples of brutality and corruption from his book, Winston then asserted that these systemic infringements went unpunished because “they were being ordered to do what they had done by their superiors and politicians.”

Winston elaborated on this by focusing on the consent decrees that various police departments were put under – except for that of Oakland. At the end of the day, however, The Riders weren’t convicted, they were only removed from the force – still, the consent decree worked to a degree.

Then, towards the end of the discussion, the conversation moved on to the differences between the way the respective police forces are structured in the United States and Turkey. It was emphasized that in countries such as Turkey and France, the force is centralized, and thus Winston claimed that this structure “makes accountability much more difficult because the weight of control you need to put in order to change police.” Winston asserted that “at a local level you can put pressure on an actor that has less influence and pull in a system, and you can push on it from multiple sides.”

The illuminating conversation ended with a wrap-up of how Winston and BondGraham wrote their book: the way they interviewed people, the way they sued the city of Oakland for hundreds of records and the way they won those records through California’s open record laws. Winston called this endeavor “investigative history,” as their aim in writing this book was to “try and build out as complete a picture of the city as possible or to surround the subject.”

As final advice to young reporters, Winston’s suggestion was “to be at a location instead of interpreting the world through a computer screen.” Because for Winston, “nothing beats actually being somewhere on the ground and really understanding the city and people that you're reporting on and communicating with.”