Panel to share lessons on providing health care in unstable times

Erick Rozo knows he should have felt nothing but joy on his graduation day in May at Columbia, where he earned a Master of Public Administration in Development Practice from the School of International and Public Affairs. The 34-year-old’s feelings that day were tempered, however, as it also marked the eighth anniversary of the day he last saw his family in Caracas, Venezuela.

Since he fled his home country, conditions have only become worse under repressive policies that have led to hyperinflation, escalating starvation, disease, crime, becoming the second-largest external displacement crisis on the planet, according to the United Nations. Rozo was fortunate after arriving in the United States, where he joined the inaugural cohort in 2019 of the Columbia University Scholarship for Displaced Students, which supports displaced students from anywhere in the world by offering them full scholarships to pursue undergraduate or graduate degrees across Columbia’s 19 schools and affiliates.

“The thing is, you never decided to leave, you had to leave,” Rozo said, describing the same predicament faced by millions of others on the planet.

More people than ever before are living in precarious situations, after leaving their home countries in order to survive, typically to escape conflict, violence and persecution as well as from the impact of climate change.

Nearly 90 million people – roughly 1 of every 88 people on the planet – are forcibly displaced worldwide, according to a June report from the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

On top of the challenges displaced people face in foreign lands is the need to ensure that health systems are adequately equipped to provide them with care. As Monette Zard, Director of the Program on Forced Migration, describes, “while humanitarian health responses typically feature early on in any emergency, over time, as displacement becomes protracted, national health systems play an increasingly important role in responding to the needs of refugees and displaced populations."

While the challenge of accommodating these new demands is formidable, particularly for health systems in fragile and low income settings, and requires collective efforts and more advanced planning, it is not insurmountable, according to a series of reports just published by a consortium of researchers from AUB, UniAndes, Georgetown and Brandeis, and led by Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, with funding from the World Bank Group, UNHCR and the U.K. Aid.

The main report – World Bank Consortium: The Big Questions in Forced Displacement and Health – focuses on health care and offers a series of findings that countries and their governments should consider before embarking on such an effort.

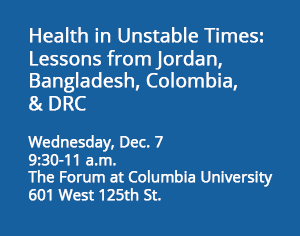

A panel of experts – including some involved in the studies – will convene Dec. 7 in person and online to discuss the issue and the findings hosted by Mailman’s Program on Forced Migration and Public Health.

Among the key findings of the main report – which included studies conducted in Jordan, Bangladesh, Colombia and the Democratic Republic of Congo – include better planning, strengthening health care systems, understanding the needs of host and displaced populations, creating better ways to pay for such efforts, and leveraging the human capital of the displaced populations to fill service gaps in the health care service.

Among the lessons learned, the report identified several factors, including: the availability of accurate and timely demographic and epidemiologic data to better understand who is in the displaced and host populations and anticipate and plan for their needs; humanitarian leadership in close consultation with national actors, including government; lowering costs to improve access to health care for displaced populations; and the vital importance of financial arrangements that are embedded in policies that support the longer-term resilience and self-reliance of refugees and displaced populations.

The report’s authors conclude that with conflicts showing no signs of abating, and protracted displacement arguably here to stay, it is critical to think about the health and well-being of refugees and displaced populations in tandem with the host populations they live alongside. The challenge is that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to this kind of crisis, according to one of the key conclusions:

“A singular or uniform approach on the part of international and national actors can never hope to accommodate the diversity of political contexts and capacity constraints that exist in different hosting communities.”

The reports’ authors explained that Colombia, Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Jordan were chosen as case studies for this analysis in order to incorporate and assess a wide variety of contexts which may factor into health service provision and financing. The selection also reflects a diversity of geographic regions and differing national policies towards refugees and displaced populations and incorporates considerations of data availability and feasibility.

The small country of Jordan has a long history of accepting refugees and roughly one in five people living in the country are Palestinian refugees. Since the civil war began in Syria in 2011, more than 1.4 million refugees from that country have fled to Jordan, which currently hosts over 760,000 registered refugees from several countries including, but not limited to, Iraq and Syria. While Jordan continues to accept refugees, the rapid increase in population has challenged national resources and infrastructure and inspired innovative approaches to international funding structures for protracted humanitarian crises.

In South Asia, the People’s Republic of Bangladesh also has a long history of hosting displaced populations. More than one million Rohingya have fled persecution in Myanmar since 1978 for Bangladesh – more than 744,000 between 2017 and 2018 – which now hosts an estimated 925,000 displaced Rohingya. With over 24 million Bangladeshis living below the poverty line, and climate change likely to exacerbate seasonal cyclones and flooding in the low-lying country, Bangladesh is tasked with building a humanitarian response that can address the needs of refugees and host community members alike.

In recent years, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has faced a series of overlapping national and international conflicts. The country hosts an estimated total of 5.5 million internally displaced persons, with an estimated 2.2 million people newly displaced due to the conflict in 2020, primarily in eastern provinces including North and South Kivu. The country has a high poverty rate and has been subjected to exploitation and extraction of resources by foreign entities and armed groups, leaving the national health care system without the resources to meet the needs of both displaced and host community members.

This case study on Colombia focuses on the two coexisting protracted migration crises: the internal forced displacement – caused by violence and the Colombian armed conflict – and the external displacement from Venezuela. While not without challenges, the Colombian government’s efforts to register and support internally-displaced individuals, alongside the relatively inclusive programming aimed at meeting the needs of Venezuelans, offer lessons and approaches which may be applicable across multiple countries and contexts.