A decades old history

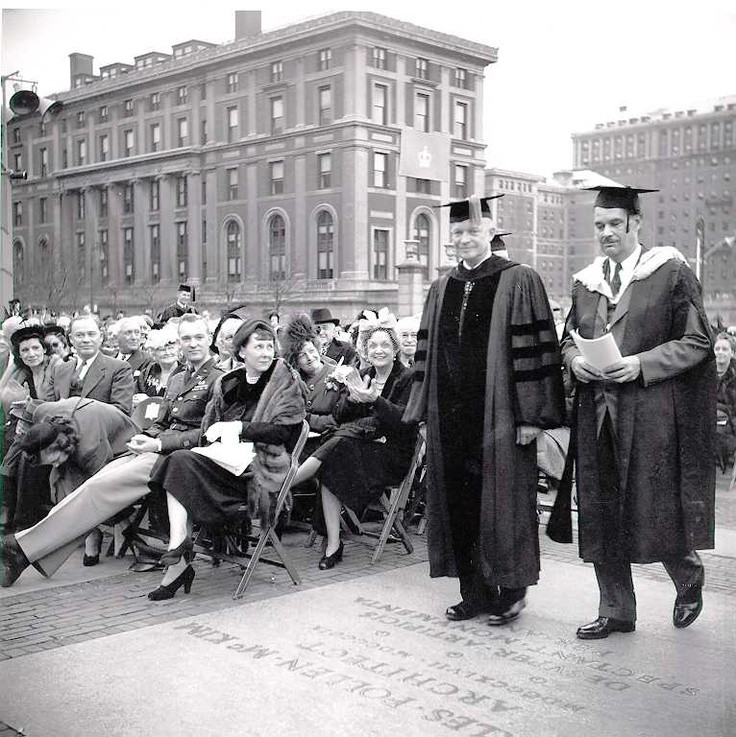

The relationship between Columbia University on one side and the Western and Northern part of Africa on the other extends beyond the past decade, years before opening the Tunis Center. It is a story of research and partnerships, institutional and human interactions, commitment and progress. The earliest connection goes back to the Second World War. Hence, during the Tunisian Campaign, Dwight Eisenhower--who later became the 13th President of Columbia University--spent several months in Tunisia. He also became the first and only U.S. President to visit the country in 1959.

Following decolonization, Columbia hosted several African students who went on to become high level officials of the newly formed postcolonial states. erefore, thanks to a U.S. State Department program funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Columbia contributed to the state building process of Tunisia by forming some of the country’s first diplomats. e first recorded graduate of Columbia is Habib Ben Yahya, who obtained a master’s degree in International Affairs from Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) in 1961. He later became Tunisia’s Ambassador to the US, then Foreign and Defense minister, and finally Secretary General of the Arab Maghreb Union.

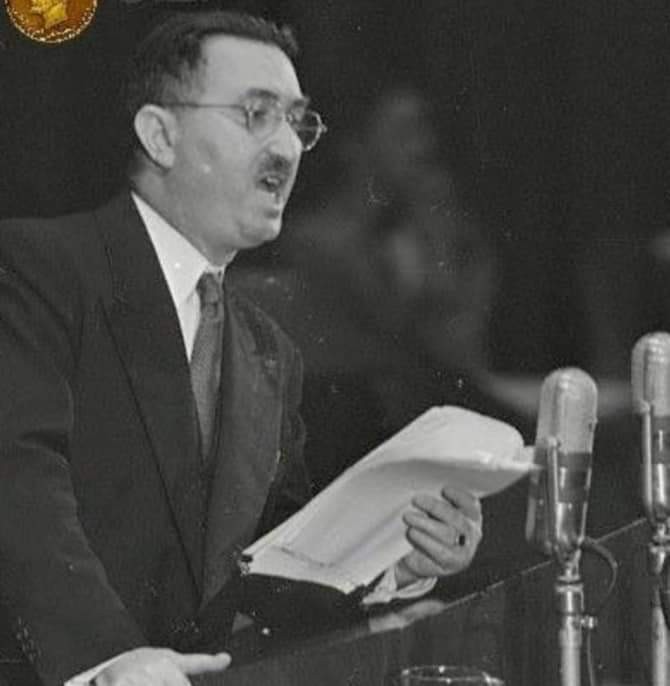

Our records show another Tunisian who graduated from Columbia previous to Habib Ben Yahya, but this scholar became a naturalized citizen of Tunisia at a later stage in life. Iraqi philosopher and stateman Muhammad Fadhel al-Jamali obtained his PhD from Teachers College in 1932. He was one of the founding fathers of the Iraqi university, several times minister, foreign minister, prime minister and the parliament speaker of Iraq. President Habib Bourguiba granted him Tunisian citizenship in 1961 after he left Iraq for exile in Tunisia. He taught in Tunisian universities and lived in Tunisia until his passing, in 1997.

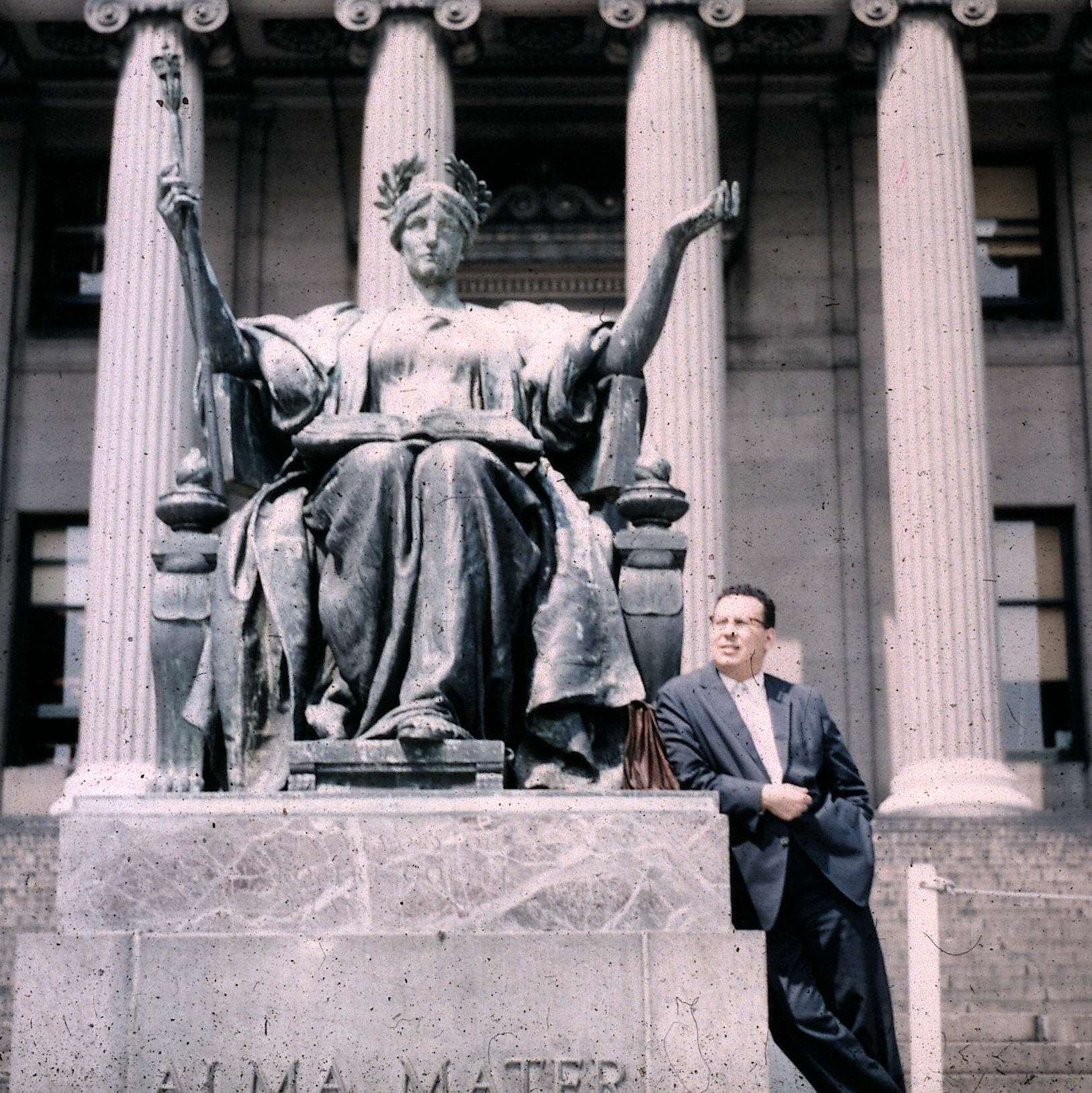

Another prominent North African alumnus is Mustapha Abdullah Baiou. He is the first recorded Libyan graduate of Columbia, graduating with a Master of Arts in History from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) in 1958. Baiou is one of the founding fathers of the Libyan system of education and a leading Libyan historian. He became the first dean of the Faculty (School) of Literature of the University of Libya, then president of the same university. Later, he was appointed Deputy Foreign Minister and also Minister of Education, but he eventually left the country after the 1969 coup and joined the United Nations.

But politics and education were only a fraction of the fields that our alumni enrolled in. In 1962 for instance, Mohammed Melehi, one of Morocco (and North Africa)'s most famous painters, joined Columbia's School of the Arts for two years as a Rockfeller Scholar. Melehi's work is exposed in Tate, MOMA, Pompidou, and other major arts museums and galleries. He is known to have "instigated a local form of modernism that mixed the avant garde of Milan and New York with the traditions of his home country, and was a founding member of what became known as the Casablanca school." (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/nov/20/mohamed-melehi-obituary). In the subsequent years, tens of students from West and North Africa were accepted at Columbia University, studying business, engineering, politics, public health, etc.

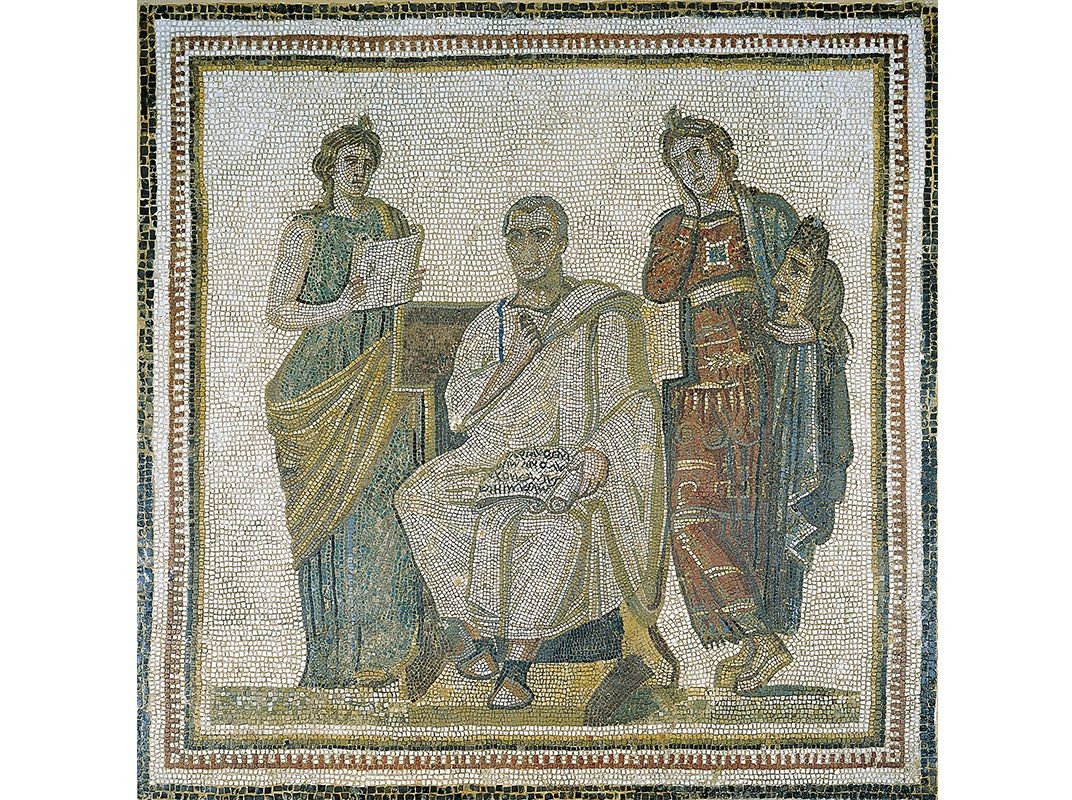

During those early years, the University hosted speakers from Tunisia and lectures about the country. A particularly notable visit was that of former Tunisian Ambassador to the U.S. and later Foreign Minister Habib Bourguiba Jr., in 1961. He spoke about Africa in world affairs at a time when African states were becoming independent--Tunisia was among the founders of the Organization of African Unity that was institutionalized two years later. Bourguiba Jr. presented SIPA with replicas of two mosaics that continue to decorate the entrance of Lehman Social Sciences Library: Diane the Huntress and the Mosaic of Virgil (writing the Aeneid), two Roman masterpieces exposed at the Bardo National Museum in Tunis. Then, in 1963, it was Mongi Slim who spoke at Columbia University. He is a founding father of Tunisia’s diplomacy, having served as Ambassador of Tunisia to the UN, subsequently president of the UN General Assembly, and later Foreign Minister (he was succeeded by Bourguiba Jr.).

Other prominent Tunisians visited or enrolled in Columbia in the 20th century, such as Drs. Abdelhay Chouikha and Salah Hannachi, the first Tunisian PhD graduates from Columbia. They graduated from Columbia Business School (GBS) in 1979 and 1980, respectively.

The relationship between Columbia University and Tunisia can be traced through the alumni. Dr. Salah Hannachi is one of the two first Tunisian PhD holders to graduate from Columbia. Prior to his time at Columbia, he received a scholarship to pursue an MBA at Indiana University, but his dream was to return to the U.S. and live in a big city. He applied to GBS after the MBA. He was accepted in 1969 and studied on a USAID scholarship until graduating in 1980. Dr. Hannachi’s dissertation was on Power and Utility Theory, applying econometrics to power. He recalls the late David Miller, Professor Emeritus of Irish and religious history at Carnegie Mellon University, and Peter Blau, Professor Emeritus at Columbia, as some of the influential thinkers and professors from that time. Being in New York City as a graduate student allowed him, among other things, to work in Wall Street. Brooklyn was his home for over a decade. When asked about his experience in New York during those years when the City was plagued by crime, he responded, “Go to the most dangerous looking people and ask them for help, you will disarm them!”

When Dr. Hannachi returned to Tunisia in the 1980s, he was appointed Dean of the Institut Supérieur de Gestion (ISG) of the University of Tunis, a first-rate business school. He used his Columbia connections to invite guest speakers and secure the latest technology for ISG, introducing IBM computers to the country. He later founded the Institut Tunisien des Etudes Stratégiques (ITES), a US-modeled think-tank at the Tunisian Presidency of the Republic. Dr. Hannachi then became Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs before being selected as Ambassador to Japan. He recalls his time in Japan and the leverage procured by his status as a Columbia alumnus: the powerful Columbia Alumni Association chapter of Japan was his best introduction to the Japanese high society.

The 2010s: A Turning Point

Columbia’s interest in the region increased dramatically after the 2011 Arab Uprisings. First of all, there was a noticeable increase in the number of applicants from Tunisia and Morocco, and subsequently of Tunisians and Moroccans studying at the University. The attention paid to Tunisia increased among Columbia scholars as well. Between 2014 and 2017, the World Leaders Forum (WLF), Columbia’s flagship speakers’ platform, hosted three Tunisian statesmen: human rights activist and president Dr. Mohamed Moncef Marzouki in 2014, Prime Minister Eng. Mehdi Jomaa in 2015, and Pr. Yadh Ben Achour, professor of constitutional law and President of the Higher Authority for the Realization of the Objectives of the Revolution, Political Reform and Democratic Transition (an ad hoc, semi-parliament established in 2011 after the fall of dictatorship) in 2017. The latter was also the first scholar-in-residence of the Columbia Global Centers.

Global Immersion: Doing Business in North Africa

Pr. Kamel Jedidi is the John A. Howard Professor of Business at Columbia Business School. Since 2012, Pr. Jedidi has visited Tunisia with 219 students through his Global Immersion course on business in North Africa. The Global Immersion program gathers students for half a term in New York City before they go on a ten-day visit to their country of focus, where they are expected to work on team projects. Pr. Jedidi’s course studies developments in North Africa since the Arab Uprisings, specifically regarding the impact of the transition to democracy on business and investment. Since 2018, the course has been conducted in partnership with Open Startup Tunisia (OST), a program that introduces mostly undergraduate students to the basics of entrepreneurship. Columbia graduate students mentor OST participants and prepare them for the Columbia Venture Competition, the annual startup competition organized in New York by GBS and Columbia’s Fu-Foundation School of Engineering.

Other similar courses have been organized in Tunisia. In 2015, Pr. John Huber taught a summer undergraduate class entitled, Democracy and Constitutional Engineering in the Middle East. It took place in Tunisia and partly in Turkey, in partnership with CGC Istanbul and the Office of Undergraduate Education (UGE) at Columbia University. It provided around 20 Columbia students and a select group of students from the region with tools to understand Political Science and the process of democratization. Tunisia being in transition, the students saw firsthand the events that were being shaped. The course took place at the University of Tunis (Tunis Business School - TBS).

In the same year, Columbia INCITE and the Center for Oral History Research started a project to record the first five years of the Tunisian revolution. The Tunisian Transition to Democracy Project consists of 58 interviews (110 recorded hours) that chronicle a multitude of events spanning from the revolutionary days of late 2010 to the relatively stable period of 2015. They are available for free on the website of Columbia University’s.

It was also in 2015 that President Lee C. Bollinger, the 19th president of Columbia University, visited Tunisia with a high-level delegation from the University including Safwan M. Masri, EVP for Global Development and Global Initiatives, who was then writing his Tunisia: An Arab Anomaly (CUP, 2018). Their visit was organized in partnership with the Tunisian American Chamber of Commerce, led by Amel Bouchamaoui. They met with the country’s political leadership, including Tunisian president Beji Caid Essebsi, the prime minister and other government ministers. They also had meetings with Tunisian political, business and civil society leaders, as well as members from the academic and intellectual community, and Columbia alumni.

That visit marked the inception of the Columbia Global Centers | Tunis, whose establishment was announced in November 2016 during the Tunisia 2020 international investment conference.

The number of Columbia graduates from West and North Africa increased during this period, from 36 in the 1990s, to 49 in the 2000s, and 76 in the 2010s. Ghana, Morocco and Tunisia are home to the majority of Columbia alumni from the region. The Center therefore works closely with the Columbia Alumni Association (CAA) to host alumni events and other activities. Alumni groups are actually active in Morocco, Ghana and Tunisia.