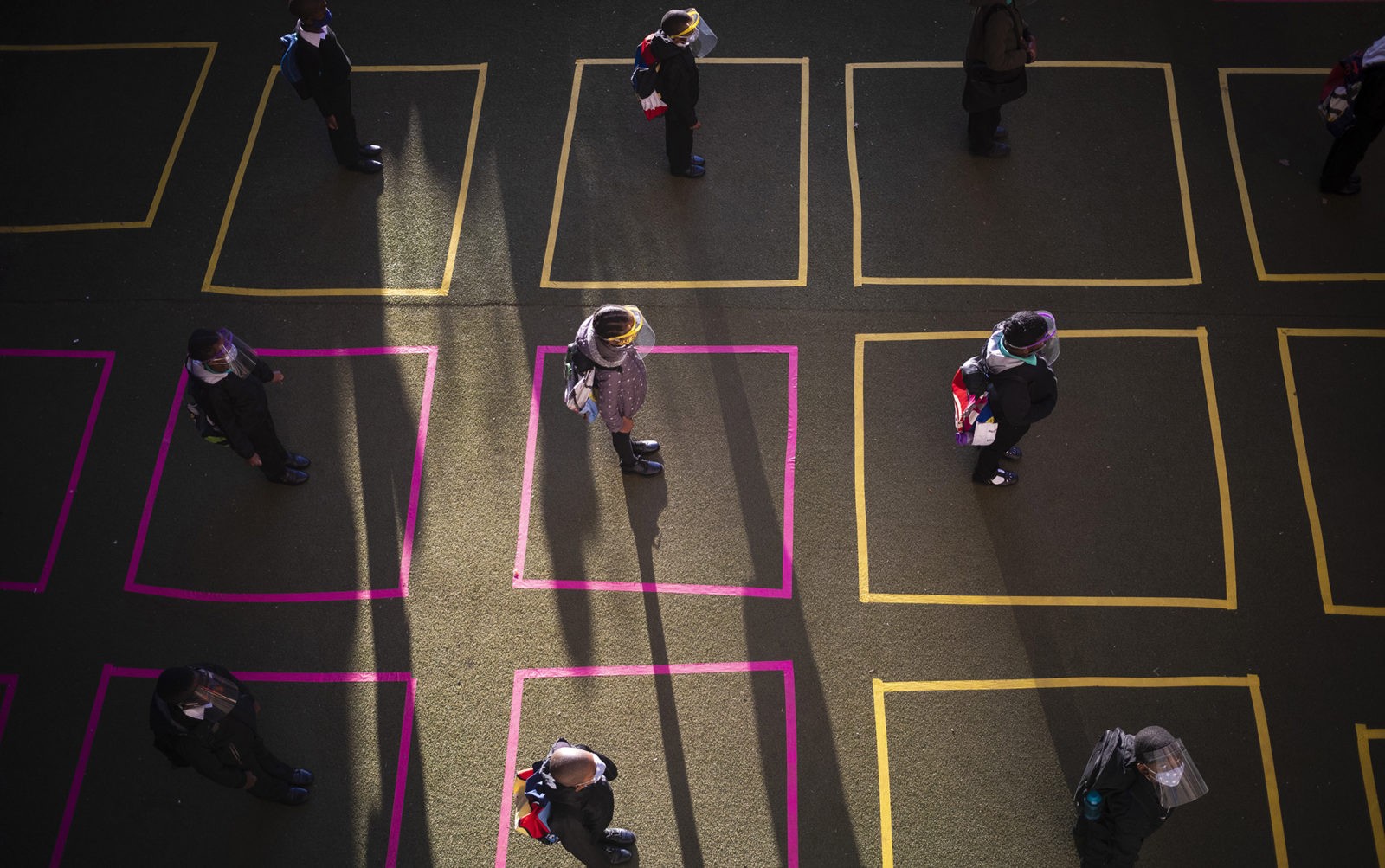

‘Copy-paste’ physical distancing measures have had ‘dire effects on developing countries’

Physical distancing is a tried and tested method of slowing the rate of infection during a pandemic (without the use of medical interventions). But as we’ve seen, it can have devastating economic, health and social effects, especially on developing nations.

Physical distancing, while essential to flattening the curve of Covid-19 infections, is a challenge for under-resourced communities. This was the consensus during a virtual dialogue around “Social Distancing in Africa and the Developing World”.

Moderated by Professor Ames Dhai, the founder and former director of the Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics at Wits University, the session included a keynote address from Dr John Nkengasong, Director for the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and a discussion among fellow panellists Amanda McClelland from Resolve to Save Lives; Chikwe Ihekweazu from Nigeria CDC; Ray Hartley from the Brenthurst Foundation and Yanis Ben Amor from Columbia University.

Speaking during the event, McClelland from Resolve to Save Lives, an initiative which among other things helps at-risk countries prepare for epidemics, said most countries adopted non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) as a first response.

NPIs are non-medical measures taken to slow the spread of illness. These are especially beneficial in the absence of a cure or vaccine for a virus, as is the case with Covid-19.

Early on in the pandemic, the success of China’s lockdown and strict physical distancing measures to slow the spread of the virus encouraged many African countries to implement the same measures.

Dr Nkengasong shared a breakdown of some of the common restrictions adopted by African countries:

- 34 countries cancelled commercial passenger flights;

- 9 closed land and sea borders;

- 14 implemented a mandatory two-week quarantine period;

- 9 had compulsory testing at the borders; and

- 33 closed educational institutions.

But McClelland points out that many “copied and pasted” methodologies and failed to adapt the measures to their context, placing heavy burdens on health systems and the economy.

“We started to see delays in access to healthcare and economic and food security issues.”

She shared a snapshot of data from community surveys conducted across 19 African Union states with more than 22,000 respondents. The research is part of the Partnership for Evidence-Based Response to Covid-19, a joint initiative with Resolve to Save Lives, Africa CDC and the World Health Organisation to help reduce the negative impacts of NPIs.

Respondents reported:

- Significant disruption to their economic and social wellbeing;

- Three-quarters of income earners recorded lower income than last year;

- Seven out of 10 had barriers to accessing food. The main cause was higher food prices and lower incomes; and

- Almost half had delayed or chose not to access healthcare services. Many with chronic conditions missed treatments, a phenomenon which was most pronounced among the poor living in urban areas.

“Though a number of governments had implemented relief measures such as suspending utility payments, giving food vouchers, cash transfer programmes, what we found in the survey is less than 85% of respondents had received any type of support from the government,” said McClelland.

Despite this, data found that support for NPI measures was high. For example, 65% of respondents agreed that banning mass gatherings was essential to stop the spread of Covid-19. More than 40% agreed it was necessary to limit movement for work and school. But on the ground, there was limited adherence to restrictions that hindered economic activity.

Hartley, the research director at the Brenthurst foundation, explained that most African economies have mostly labour-intensive industries making them extremely vulnerable to the negative impacts of physical distancing. “Whereas you can work from home when you’re in banking, you can’t work from home if you’re in agriculture or in mining.”

At the same time, workers in these sectors are at high risk of exposure to the virus.

The informal sector was also hard-hit by the lockdowns. “These are people who are dependent on foot traffic for livelihoods, they don’t have savings overall,” he said

In South Africa, the informal sector accounts for almost 26% of total employment (traders at 17.8% and household or domestic workers at 8%) according to StatsSA’s latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey.

“We have to think carefully about how to balance heavy attempts to impose social distancing without crashing the parts of the economy which are relatively underrepresented and voiceless,” said Hartley.

Dhai emphasised that while governments have made admirable strides in the fight against Covid-19, the pandemic has also been fertile ground for corruption.

South Africa is dealing with the aftermath of funds looted from the R500-billion Covid-19 relief fund. Recently four top officials from the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) were suspended after gross maladministration of the Temporary Employer/Employee Relief Scheme (Ters) payments were discovered. Daily Maverick’s Scorpio unit also uncovered that the Gauteng Department of Health bought PPE at a cost of more than R500-million above market prices.

“It is important that when social distancing policies are enacted by our leaders, no population group must be prejudiced,” said Ames.

“Social and economic injustices (that) were perpetrated in the name of public health, has had long-lasting repercussions. We’ve ended up with food insecurity, health insecurity, job losses, reduced income and the list will go on.”

Ames said special interest must be taken for safeguarding vulnerable populations such as the homeless, undocumented migrants, and those with chronic illnesses.

“We need credible public health authorities and we need credible political leaders.”