Montparnasse in 1912: Territory of a new modernism

Undoubtedly, Paris is not unique as a center of these profound movements affecting arts and thought in pre-war Europe. But in this aesthetic storm, Paris-Montparnasse, more than any other capital, created a mythology, where gold, art, and filth mingle.

This article is extracted from the inauguration program for the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc. You can view the full program here, and read the article in French here.

1912! Ah! If only Reid Hall’s Grande Salle, opened to the public that year, could speak... The Belle Époque, which ended in the years preceding the catastrophe of 1914, was not at all aware that it was “belle.” Even if, though tragically ironic, contemporaries proclaimed that the twentieth century would be the one “to end all wars”! The chrononym only appeared after the war, inspired by nostalgia for a euphoric period, in the wake of the 1900 World’s Fair.

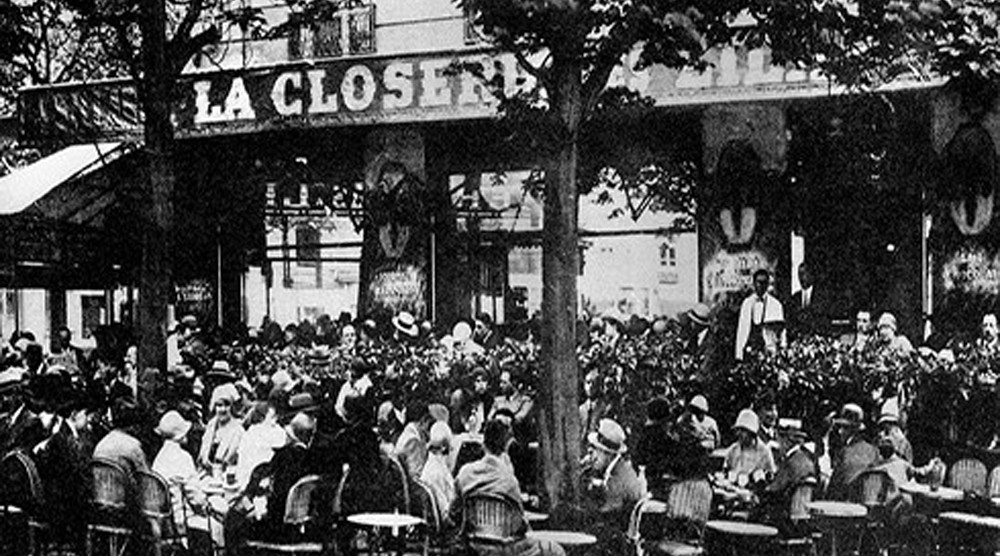

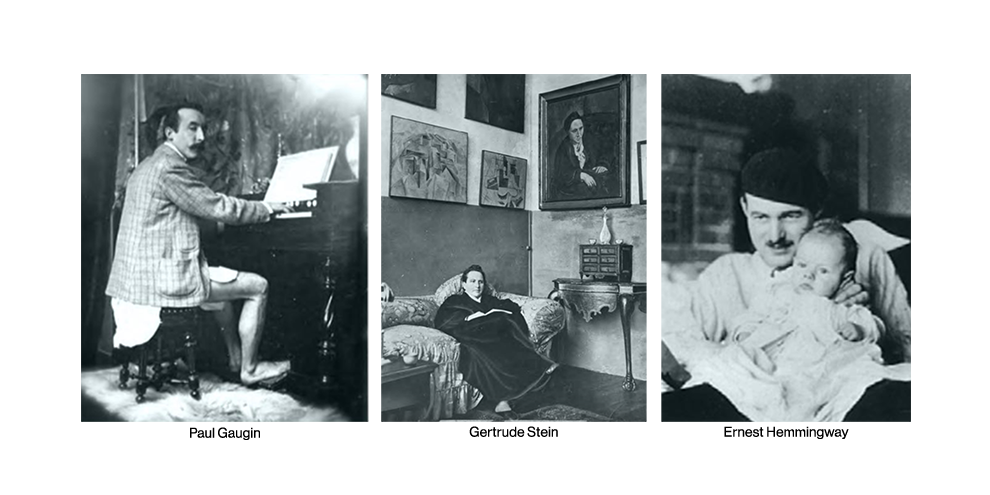

Reid Hall is nestled in the Montparnasse district, in the heart of the territory of a new modernism. Here reigns an intense cultural and artistic effervescence. The salon of the avant-garde writer Gertrude Stein (and her brothers), 27 rue de Fleurus, is a few blocks away near the Luxembourg Gardens, and the poet, Ezra Pound, is domiciled on rue Notre-Dame des Champs; the two boulevards, Raspail and Montparnasse, intersect at the mythical Vavin crossroads; academies, old like the Grande Chaumière or very recent, like the one launched in 1911 by the artist Marie Vassiliev, welcome those who dream of becoming artists; the the salons of the Closerie des Lilas and the terraces of the Dôme and the Rotonde (taken over in 1911 by a picturesque entrepreneur, Victor Libion, who offered food and drinks to their artist clients), host a worldwide diaspora: American, Latin (the Argentine tango replaces the polka!) but mostly Slavic. La Ruche, a little further on, in what was once the former wine pavilion of the World’s Fair, hosts armies of painters, some of whom, like Léger, Picasso, Chagall, Soutine, and many others, would soon achieve world fame. Montparnasse, the new Babel, spoke all languages and reinvented all aesthetic languages... a whole ecosystem was set up on the “Left Bank” that welcomed foreigners, whether they were attracted by the brightness of the “City of Light” or driven away by the pogroms in the East. A little later, after the war, Americans, including those of the “lost generation” (first and foremost Francis Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, who lived just a few steps from Reid Hall, also on rue Notre Dame des Champs), fleeing Prohibition and, for some, the Ku Klux Klan, flocked to the city – Paris was a party! – and became one of the largest foreign communities in the capital before the 1930s. Sylvia Beach ran a bookstore and publishing house, Shakespeare and Company, at 7 rue de l’Odéon, published a thousand copies of Joyce’s Ulysses in 1921. “You will never sell a copy of Ulysses, that book is so boring,” Joyce told her. With these literary geniuses, Montparnasse was then the crucible of a profound reinvention of Anglo-Saxon literature.

The arts, the rebellious spirit, the poetry – all had until then taken up residence at the end of the nineteenth century on the right bank, on the Butte Montmartre. The “Hydropathes,” the “Zutists,” and all the subversive spirits of Paris, after the Commune, used to meet there in cafés and restaurants. The “Apaches” – those of the film Casque d’or – the balls attended by gentlemen in top hats, and the cocottes, the dancers, the prostitutes who were friends of Toulouse-Lautrec, the Bateau-Lavoir where, in 1907, Picasso created his Demoiselles d’Avignon – all this made up the physiognomy of an artistic life concentrated within the perimeter of a village, with its mills, its alleys, and its folklore. With the very urban character of Montparnasse and its cosmopolitanism, art and spirit will change in scale. The mind is never satisfied with ideas alone, it needs something concrete. Impressionism could be said to emerge with the invention of portable oil-paint tubes? In these years, the mind is fueled by electricity: the electricity that allows the inauguration of a new metro line in 1910. Montmartre is connected to Montparnasse! The north of Paris to the south – which would inspire the poet Pierre Reverdy a few years later to title a new monthly literary review, NORD-SUD. As Apollinaire wrote, “Montparnasse is already replacing Montmartre. Alpinism for alpinism, it is always a mountain, art on the summits.” The lyricism of the poet makes him neglect the fact that between the two peaks, there is a difference in level: one is a true hill that provides the most beautiful view of the capital; the other, an artificial bulge, a modest rise of relief generated by rubble. Thus the spiritual geography of Paris changes. Artists leave the village for the city, and notably, as an emblematic sign of this inner migration in 1912, Picasso leaves Montmartre to settle at 242 boulevard Raspail, a stone’s throw from Reid Hall. In fact, after the first modernity – that of Impressionism –now “installed” and consecrated at the time of the World’s Fair, a young generation sought to invent another. It began in Montmartre – notably with the Demoiselles d’Avignon, in the first expression of Cubism – but exploded later in Montparnasse...

Modernity is defined by machinery – even if in 1912, it is a machine that “failed,” with the sinking of the Titanic in the icy waters of the North Atlantic. In Montmartre, there was no train station, but in Montparnasse, the train triumphed. On October 22, 1895, a locomotive crashed through the station’s security gates, as if to symbolize the smashing entry of modernity into Paris, and ended up suspended above the void, pointing toward the rue de Rennes. One couldn’t imagine a stronger image! It is the machine, it is energy, it is speed, all of which penetrate not only the city but the twentieth century as well. A few years later, in 1909, the Franco-Italian poet Filippo Marinetti published his Futurist manifesto – a celebration of speed –in the Figaro newspaper. Unexpected effect? The philosopher Bergson, in his essay Le rire, which salutes the new century, advances the curious idea that laughter is “mechanics applied on the living,” in other words, a machine exerting itself on the human! The studies of chronophotographs by Jules Etienne Marey, which deconstruct the movement of a man’s walk, were nothing other than proof of the biomechanics of movement... In 1912, Picasso, Braque, and Apollinaire (who founded with the poet André Salmon, on boulevard Raspail, the journal Les Soirées de Paris) haunted the workshops, academies, and terraces of Montparnasse. The two painters “push” the logic of cubism to its “analytical” pinnacle. The real is “analyzed” in squares, circles, rhombuses – as if creation derived from a mechanical factory of geometrical forms. Images, multiplied by a mechanized an increasingly powerful press, invade print media and cover the walls of Paris. A true culture of street images opens a new chapter in modernity. Posters and newspaper pages find a place for themselves in collages and cubist canvases, even participating, in 1913, in the new mechanisms of poetic writing Apollinaire implements in the poem Zone. First “writing machine” before the emergence, with surrealism, of automatic writing...

Historians are rightly suspicious of history by dates – the effect of a distorted magnifying glass that betrays reality, often generating meanings born of a retrospective illusion. Yet, despite these warnings, I cannot help but distinguish this period by years. Much takes place in 1912. Perhaps because for some superstitious people the number 13 is cursed, one should remain at 12? Like the poet d’Annunzio who, in 1913, dated the dedication of one of his books with “1912+1”. Is this a reason to avoid 1913 – the last stop before the “storms of steel?” That year, Paris is shaken by three events that will have major effects on the century. The premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in May, with Diaghilev’s Russian ballets, choreographed by Nijinsky, was a manifesto for a new music. The publication of the first volume of À la recherche du temps perdu, Du côté de chez Swann (self-published through Grasset in the Saint-Germain district) redefined literature. The creation of the first ready-made, Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel, which the artist bought, like most of his objects, at the BHV – near the Marais – changed the paradigm of art...

Undoubtedly, Paris is not unique as a center of these profound movements affecting arts and thought in pre-war Europe. At this same time, the zeitgeist inhabited the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, where the Dadaist movement was brewing, as well as Dresden and Berlin, the homelands of Expressionism, and Brussels, with the Art Nouveau movement that wanted “art in everything...” But in this aesthetic storm, Paris-Montparnasse, more than any other capital, created a mythology, where gold, art, and filth mingle. There are dealers and patrons like the Steins – a whole new market! There is also extreme destitution. A doctor removes a nest of bedbugs from Soutine’s inner ear, a resident of La Ruche and a regular visitor to the Rotonde! These small anecdotes, a real mental heritage of this period, all capture liveliness at that time. The visitor from overseas, such as those studying, creating, or conducting research for a few months at Reid Hall, can meet, every night, the ghosts of this dream age - much like the character in the film, Midnight in Paris by Woody Allen. Perhaps they will carry back with them the brightness of this time in their eyes...

Thierry Grillet is an author and curator.