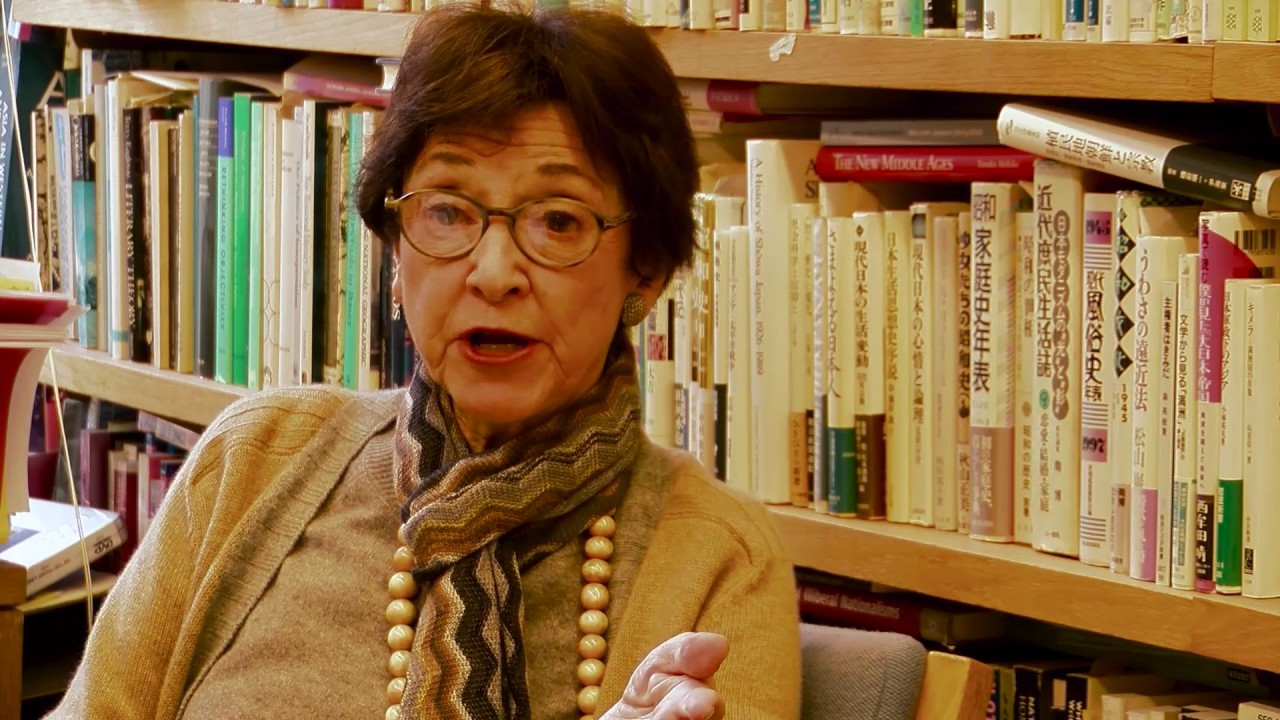

Q&A with Professor Carol Gluck

Q – Why have you chosen to base the next Politics of Memory event in Istanbul and Amman? In what ways do perspectives from Istanbul and Amman add to the Politics of Memory in Global Context project?

Gluck – The theme remains but the topics change as we move our project to different locations: hence, the World Wars in Paris, the Armenian genocide in Istanbul, the multiple depredations in the Middle East in Amman.

In October we will be at the Global Center in Beijing, tackling what Chinese and Koreans call Japan’s “history problem” – official views of Japanese actions during World War II in Asia. We take our title from the joint Sino-Japanese communique of last November which pledged “To Face History Squarely.” We’ll see how “squarely” things turn out.

In each case we have participants from different places, bringing perspectives on other topics: in Beijing, other “history problems,” such as those in Poland and Russia, for example. In Istanbul and Amman, our speakers come from France, Japan, South Korea, Lebanon, Turkey, and the United States, a representative sample of global thinking.

Q – The panels for each of these events include people from diverse fields. How do you envision each of these conversations coming together?

Gluck – The cross-disciplinary talk really works now. We’ve been doing it long enough for the social scientists and neuroscientists to understand one another’s language and appreciate one another’s perspectives. This kind of connection is the direction in which memory studies are going; we were early to the party but there’s still a long was to go. We are fortunate that Columbia has some of the most important cognitive neuroscientists and psychology working on memory.

On the museum side, curators pay far more attention to scholars than they once did, but the demands of public history are often contradictory and always political, as we saw during the years of work on the 9/11 museum: the pressures from the families, the rescuers, the politicians made it impossible to present a narrative that could be anything other than partial and patriotic. But my goodness, they did try!

Q – Can you describe the thematic thread that weaves through these three events as well as how they will be distinct from each other?

Gluck – The common thematic thread of the three Think-ins winds around the national and international political tensions in public memory and the relation between individual and collective memory of traumatic events carried over time to subsequent generations (World Wars on the battlefield and the home front, the Armenian massacre, colonial violence, the Naqba, the Holocaust, the massacre of Koreans, rebellions, etc.).

The Think-ins are different, not only because the individual topics change but also because of the local context: the World Wars remain vivid in the different religious and ethnic precincts of Belgian memory; events like the Armenian massacre mean something different in Turkey than among the Armenian diaspora.

Q – How does this fit into the mission of the Committee on Global Thought and what is the aim of these think-ins and workshops?

Gluck – Our mission is to think differently about the world we live in. The politics of memory is a flammable issue in many places, not well understood even as it creates conflict and hostility – and occasionally consensus, even reconciliation. The aim of the symposia, workshops, and Think-ins is to bring people together who would otherwise not be in the same room and provoke them to think together about these issues: how to understand them and how to manage them.

Q – What role have the Global Centers in Istanbul and Amman played in helping bring these events to the public?

Gluck – The Global Centers in Paris, Istanbul, and Amman have been wonderful partners in planning and hosting these events. The directors and staff in Istanbul and Amman have found locations, suggested regional participants, arranged travel details, and generally provided the local energy to accomplish what would have been difficult, probably impossible, for us to do by ourselves. They have proved the value of the Global Centers in providing a venue for extending and expanding Columbia’s intellectual and practical presence: for connecting Columbia to the world and the world to Columbia.

Q – What accounts for the growing interest in memory studies in recent years, and how do you see the field developing in the future?

Gluck – The explosion of memory studies over the past three decades followed the surge of interest in memory that began sometime in the 1970s in many places, whether connected with the Holocaust and World War II, transitional justice in Latin America, national patrimony in France and elsewhere, past injustices and present rights in the case of slavery, indigenous peoples, and the like.

There are lots of explanations for this surge of memory, which is in itself nothing new: what is now called memory used to be called history or identity. Some say we are mired in memory because we have lost our sense of the future and have nowhere to turn except the past. Others say that social change brought more actors on to the memory stage, calling for their stories to be included in the national drama. I sometimes quote Hamlet in this regard: people claiming “rights of memory” in their kingdom. Whatever the reasons –and they are surely multiple – memory is a huge issue today for individuals, families, ethnicities, and nations.

“Memory studies” is a growing academic industry all over the world. Too much memory, one might say, but it is the coin of our age, and its politics has real, often nasty, consequences. The lack of attention to policy is part of what drives our project: we want both to better understand how memory operates and also how to manage its politics better.