Restoring Reid Hall’s Grande Salle in the Spirit of the Belle Époque

At long last, the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc is once again ready to welcome students, faculty, staff, and guests – its luster restored and its spirit rekindled, the heart of Reid Hall beating into its 110th year.

This article is extracted from the inauguration program for the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc. You can view the full program here, and read the article in French here.

During the reign of Louis XIV, the rue de Chevreuse was merely a footpath nestled in the heart of the orchards overseen by the domain of the abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. At its end, the southern enclosure of Paris, which would later become the Boulevard du Montparnasse.

The first recorded buildings along this path, small factories and warehouses, seem to have appeared in the middle of the eighteenth century. In 1800, the Dagoty brothers established their porcelain atelier at 4 rue de Chevreuse and, until 1823, benefited from great notoriety, even obtaining the support of Empress Josephine who authorized Pierre Louis Dagoty to sign his porcelain: “Manufacture de S.M. l’Impératrice, P.L. Dagoty à Paris.”

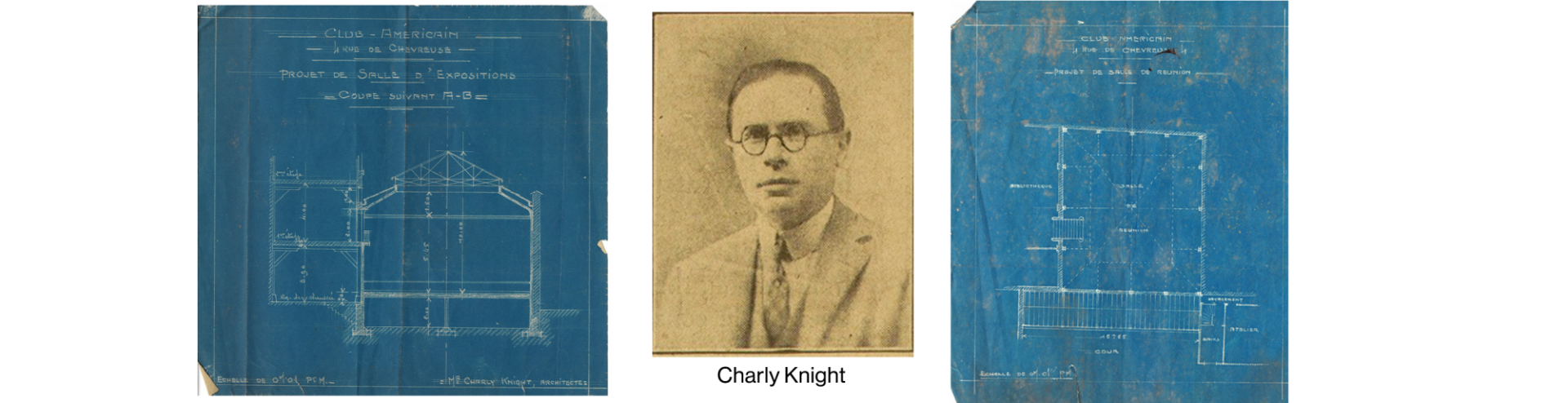

Born of a family of artists, and sons of the famous court painter Jean-Baptiste André Gauthier Dagoty, the two brothers were themselves recognized for the quality of their refined Greco-Roman decorations. They thus prophetically christened the rue de Chevreuse under the sign of the arts. When production at the atelier ceased, the building was modified for the creation of the Keller Institute, the first international Protestant school established in France since the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. In 1892, the boarding school closed and American philanthropist Elizabeth Mills Reid became interested in the site. She found it to be the ideal place to create “The Girls’ Art Club”, intended to house American women artists in the heart of the intense cultural life of the Montparnasse district. The great success of the Club allowed her to eventually purchase the site, as well as an adjacent property in 1911. She then commissioned an annex to be built, which included seven artist studios overlooking the garden. This building now houses the Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination. At this same time, the Grande Salle was built – a bridge, of sorts, between the building that had already existed, and the newly completed annex. Chosen to design the room was Charles Meissonier Knight, known as Charly Knight, an architect of American origin, yet heavily influenced by French culture. Born in Poissy in 1877 to American Parents, Charly Knight was trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, which opened the doors to many private commissions from the American intelligentsia in France, also known as the “American Colony”. In addition to his French education, Knight also inherited French artistic lineage. His father, Daniel Ridgway Knight – a famous painter who had lived most of his life in France and had worked in the private studio of Ernest Meissonier.

An analysis of his work on the Grande Salle reveals this dual influence: from his education at the École des Beaux-Arts, he retained a taste for classical and rigorous composition, striving to find symmetry and a relationship of scale in the interior volume of this connecting building where the different decorative registers are carefully hierarchical. The ensemble converges over the chimney, adorned by a semicircular relief inspired by neorenaissance models.

The general appearance of the decorations, however, reflect many Anglo-Saxon influences that show the ornamental renewal in the Parisian architecture of the 1910s. The friezes of grapevines and the geometric patterns of the woodwork lean toward a decor inherited from the Arts & Crafts movement. In the same way, the composition of the paneling, in the neo-Tudor style with large square frames, and their treatment in natural waxed tint, is very far from the style of French woodwork, which is more vertical and generally painted.

These multiple styles combined created a new architectural approach, which echoed the hotel brasseries and bars that were developing at that time in the Paris of the Belle Époque. If today the room is mainly used for conferences and concerts, it was, in fact, initially conceived as an exhibition hall, and sometimes even used to host large banquets.

The large glass roof, lined with a frosted glass ceiling subtly filtering the daylight, evokes the restaurant of the Hôtel Lutetia, designed the year before the Grande Salle, and many other emblematic places of the Montparnasse district. The spotlights that illuminate the ceiling’s periphery pay tribute to the cabarets and music halls across the Atlantic –this taste for electric lighting, becomes an essential component of the architecture and its decor.

On the eve of the First World War, the appearance of this cosmopolitan neighborhood was no longer solely French but international, much like Reid Hall, a symbol of French-American friendship.

After more than a century, the management of Reid Hall made the decision to renovate the Grand Salle, as it had lost much of its former luster: the glass panels of the roof had become dull, and numerous leaks had been repaired by opaque patches masking the daylight; the interior decorations, having been regularly repainted and waxed, had lost the subtlety of their design; differing and contradictory technical devices had been added, without much coherence, all of which had become obsolete; and finally, the absence of ventilation – especially given the recent pandemic – underscored the need for efficient air circulation in a space that frequently receives the public. All told, the general atmosphere of the room had lost a great deal of the festive and welcoming character of its origins.

As the architects of this project, we performed several diagnostic tests in order to guide the restoration process. The first was to examine the metal structures of the glass roof, determine their wear and tear, and their capacity to support more efficient glazing. At the same time, thermic studies allowed us to evaluate the air circulation needs, and to better calibrate the treatment of the room: glazing, insulation, etc. We also conducted a general audit of its acoustics and audiovisual equipment in order to determine how to best adapt these installations to the room’s multiple uses. To understand the previous changes to the room’s decor, interior decorators performed a stratigraphic study of the walls, woodwork, and ceiling in order to identify, layer by layer, the paint colors and varnish tints applied at different periods of time. The study provided more reliable data than archival images, thereby allowing us to reconstruct the room to its original state.

The combined results of these diagnostic tests enabled us to envision a general restoration plan.

Our first priority was to ensure the durability of the structure. We therefore replaced the glass panels of the roof, and also waterproofed its metallic frame. These reinforced panels and frame were then thermally treated in order to provide more efficient protection against the elements. At the same time, an HVAC system was installed in the basement and in the adjacent spaces for the treatment of the air, reusing the original radiator niches and technical voids in the room so that the equipment remained completely discreet.

Equally as important was to recentralize the Grande Salle as the primary gathering place on the property. At the crossroads of the classrooms, gardens, and offices of the Institute, its role, yet again, acting as the interface between Reid Hall and the students, faculty, and general public.

For this, we were determined to find ways in which the room could respond to the varying needs of each type of event. Storage was of primary concern. This was achieved by annexing a neighboring space and converting it into three distinct areas: the first, a place to house chairs and materials; the second, a “green room” for performers; and the third, a small recording studio for podcasts and videos. The fireplace and its relief, central to the decor of the room, were completely abraded to reveal the original stone and plaster designs, and new, dimmable, low consumption LED lighting fixtures were installed above and around the glass ceiling and affixed to the wood paneling.

Our final goal was to restore the warm and welcoming atmosphere of the room. For this, the architectural choice we made was to soften the contrast between the woodwork and the walls and ceilings: the former had been progressively darkened by layers of varnish, while the walls and ceilings, on the contrary, had been progressively repainted in white, as opposed to the original golden beige. The friezes were repainted in the style of William Morris and the Belle Époque, and efforts were made in the foyer to gently transition the color scheme from the gardens into the room.

After replacing and redesigning the worn parquet floor, the finishing touches were applied to the varnish of the woodwork, the walls, and the friezes, completing the restoration and renewing the room’s original harmonious atmosphere.

At long last, the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc is once again ready to welcome students, faculty, staff, and guests – its luster restored and its spirit rekindled, the heart of Reid Hall beating into its 110th year.

Matthieu Gillet is a heritage architect, charged with the restoration of the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc for Perrot & Richard Architects.