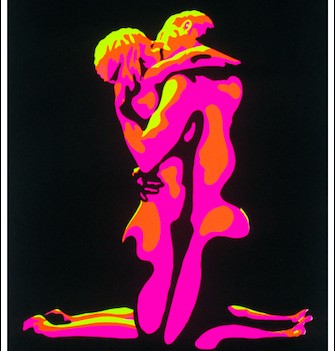

Sex after '68

A conference organized in partnership with the University of Kent Paris School of Arts and Culture examines the legacy of May '68 in contemporary sexuality.

1968 is a year brought up and constantly re-examined in academic and artistic circles in France. As most already know, the year marks a period of demonstrations, strikes, protests, and student occupations in France, with the period – referred to as ‘May 68’ – seen as a cultural turning point and social revolution for the country. Much has been written, filmed, and discussed about ’68, but, whilst important to explore and document, the focus on what happened during ’68 often overshadows what happened after.

The ‘Sex after ‘68’ conference, a collaboration between the University of Kent Paris School of Arts and Columbia Global Centers l Paris, reconsidered the year in light of more contemporary developments, focusing not on the period itself but its effects on the years that followed. Taking place at Reid Hall, the conference hosted an array of speakers from universities across the UK and Paris. Focused on the specific topic of our understanding of sex after May ’68, guests were encouraged to think of ’68 not as something that had a rigid start and end date, but rather as a series of events that continue to shift and influence our culture even today.

With a diverse range of speakers, including Michèle Idels of Éditions des femmes and the University of Kent’s Jeremy Carrette, the conference covered an array of perspectives and ideas over the course of the day. Exploring theory, philosophy, literature and audio visual art surrounding gender, the robotic self, and queer and trans theory, the conference offered the opportunity for accessible and engaging conversation surrounding the world’s shifting attitudes towards sex.

The day began with the University of Kent’s Dean for Europe Professor Jeremy Carrette introducing speakers and guests to the events of ’68 by exploring how it has been framed. Using Lessie Jo Frazier and Deborah Cohen’s framing and examination of ’68 in their book Gender and Sexuality in ‘68, Carrette argued it is important to question and challenge what the period represents in the history of sexuality. Moreover, Carrette argued, just as we frame time, we also frame our bodies and our minds, an idea that would reappear in Michèle Idels following talk.

Throughout the rest of the morning and afternoon, speakers continued to tackle challenging and complex approaches to the conference’s topic. In a talk exploring queer theory, Bee Scherer, Professor of Religious and Gender Studies at Canterbury Christchurch University, drew a parallel between the Othering of women’s and transwomen’s bodies and the framing of history by drawing on Foucault’s assertion that, ‘the history of madness would be the history of the other.’ Declan Gilmore-Kavanaugh, a Senior Lecturer in Eighteenth-Century Studies at the University of Kent, also brought a critical eye to how history is framed and remembered. Gilmore-Kavanaugh noted the importance of the year proceeding ’68 due to the June 1969 Stonewall riots. Gilmore-Kavanaugh emphasised that it is dangerous to hold events like those that took place in ’68 and ’69 as pillars of history where certain ideas begin and end. By doing so, it means the collective culture thinks of history and sexuality as concepts that have stopping and starting points rather than containing lived, continuous experiences.

In his following talk on love, Carrette correctly stated that ‘love is confusing.’ In his talk, he charted the complexity of love and its relationship to pleasure, history, and consciousness. Drawing on Plato, Carrette argued that love makes most sense when both turned into an art form and when searched for in interactions rather than in words. Loren Wolfe, Senior Program Manager at Columbia Global Centers l Paris, returned to finding love in, and through, words in her compelling talk titled ‘1968: Speed, Sperm, and Leisure.’ Using the works of Houellebecq, Wolfe established the intimate exchange between the body of the reader and the text of the writer. In spite of Barthes’ ‘slaying’ of the author, Houellebecq continues to live thanks to the relation between word, body and mind. There is power in reading slowly.

Finally, to conclude the evening Alex Goody, Professor of English at the UK’s Oxford Brookes University, focused on visual representations of sex after ’68 to close the conference. Focusing on the cyborg and the robotic in film and television, Goody charted the evolution of the sci-fi robot throughout cinema, concluding with a detailed and fascinating analysis into the purpose of female robots in recent films including Blade Runner 2049 and the television series Westworld. Goody’s talk carefully dealt with questions on what makes us human and who, or what, we fall in love with, noting that as technology evolves, so will our ways of communicating intimacy.

This final thought, that everything from sex to history is changing and evolving all of the time, was the most apt way to end a conference that repeatedly highlighted the complexity of our understanding of time and history. Not only does ’68, and how ’68 has been framed, influence our understandings of intimacy today, but also our own understanding of how the present day influences how the past is framed.