Tribute: Maryse Condé

Maryse Condé (February 11, 1934 – April 2, 2024) was a Guadeloupean novelist, critic, playwright, and Professor Emerita of French at Columbia University.

Maryse Condé (February 11, 1934 – April 2, 2024) taught for over a decade in the Department of French at Columbia University. Her writing and scholarship were essential to the transformation of “French studies,” once centered exclusively on metropolitan French literature, now often referred to as “Francophone studies,” a field that explores French language, literature, and culture from many countries.

During her tenure at Columbia, “She deployed an enormous activity organizing public events for students and scholars [...], and single-handedly established the field of Francophone literature at Columbia,” recalls Pierre Force, Professor of French and History at Columbia.

One such student is Maboula Soumahoro, associate professor in the English Department of the University of Tours, who, with Pierre Force, discussed their friendship and teaching experiences with Maryse Condé in a Library Chat, hosted by the Institute for Ideas and Imagination in Paris. They spoke about her unclassifiable œuvre, her significant contribution to Caribbean, African, and women's literature…and her great cooking.

As a Fellow at the Institute for Ideas and Imagination, Maboula Soumahoro is currently working on a screen adaptation of Maryse Condé's novel Ségou. On Thursday, April 4, she will discuss this work-in-progress in a public lecture as part of the SNF Rendez-vous de l’Institut. Register here.

Maryse Condé was born in Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe. After moving to Paris to begin her studies, she lived in West Africa for twelve years, teaching French at various levels, before moving to London to work for the BBC. She returned to France in 1973 and took her doctorate in Comparative Literature in 1975 at Université de Paris III (Sorbonne Nouvelle), under the direction of René Etiemble. She published her first novel, Hérémakhonon, in her forties, and she would go on to publish more than 20 books over the course of her career. She is perhaps best-known for her historical novels Ségou (1984 –1985) and Moi, Tituba sorcière noire de Salem (1986). Her last novel, L'Évangile du nouveau monde, was published in 2021. Professor Condé was recognized twice by the French government. She was made Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 2014 and was awarded la dignité de grand-croix de l'ordre national du Mérite.

Her former colleagues remember her as someone who was generous with her time in spite of her enormous activity as writer and scholar. “Maryse Condé was a loyal friend who remained in close touch with former colleagues after she retired,” recalls Pierre Force.

Maryse Condé often visited Paris and Reid Hall throughout her time as professor at Columbia.

Former director of Reid Hall Danielle Haase-Dubosc and then-Provost Jonathan Cole created The Columbia University Institute for Scholars, in cooperation with the Maison des Sciences de l'Homme. The endeavor lasted from 2001 to 2010. Professor Condé spoke at the inaugural conference, "On Inequality," on March 28, 2002, together with Mireille Delmas-Marty, University Paris I, Panthéon Sorbonne, and Edward Said, Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. Her talk was titled: "Des Cannibales et autres monstres: Les hommes naissent-ils égaux?" (Read the speech in French or in English)

On March 26, 2019, the Paris Center hosted a celebration of Professor Condé’s work on the occasion of her winning the 2018 New Academy Prize in Literature. (No Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded that year, due to a scandal within the committee, and so the prize awarded was thus described as the “alternative Nobel.”) Critics, activists, and students participated in a full-day conference, which concluded with a speech by Christiane Taubira, former French Minister of Justice. The event was organized by Professor Kaiama L. Glover, a former Fellow of the Institute for Ideas and Imagination, and Professor Madeleine Dobie.

This bilingual celebration sought to introduce Maryse Condé’s work to a new generation of French and American students. The day began with a private meeting between Professor Condé and students of the Columbia Undergraduate Programs in Paris who posed a series of questions about her novels and writing process.

Image Carousel with 3 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: Maryse Condé (center, wearing sunglasses) with Columbia in Paris undergraduate students in the Salle de Conférence at Reid Hall.

-

Slide 2: Christiane Taubira greets Maryse Condé in the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc.

-

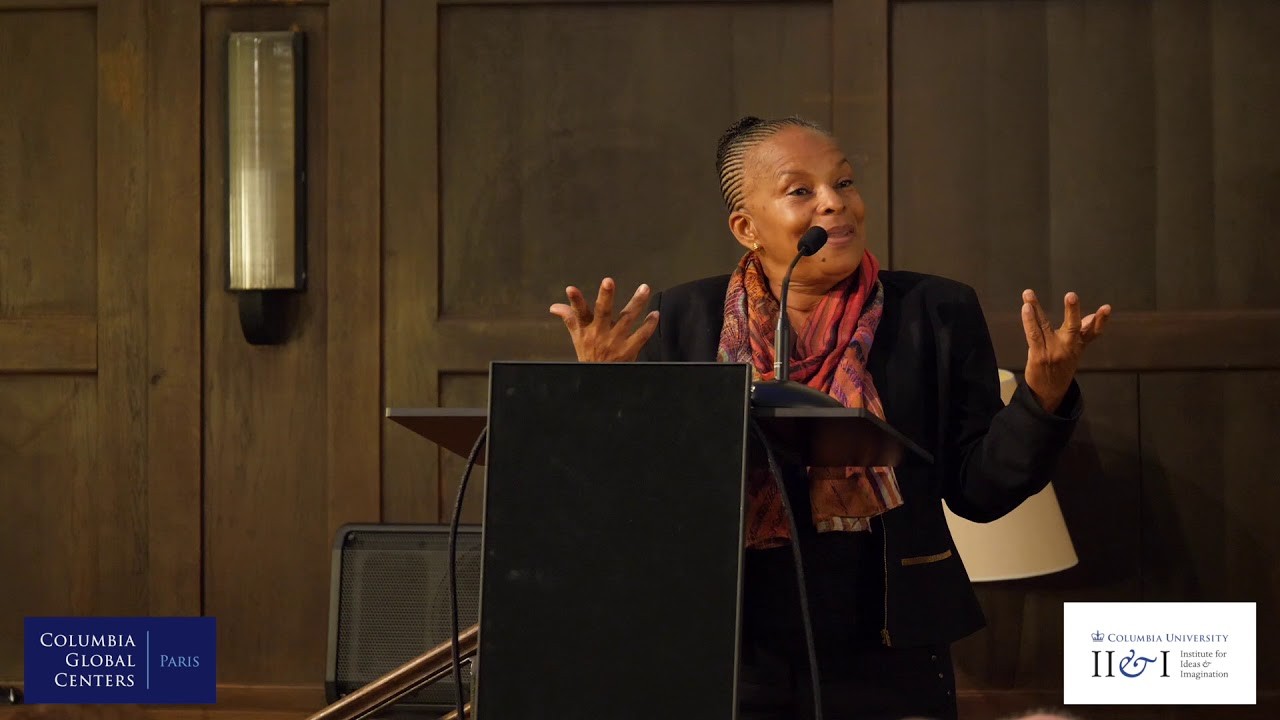

Slide 3: Christiane Taubira at Reid Hall.

Maryse Condé (center, wearing sunglasses) with Columbia in Paris undergraduate students in the Salle de Conférence at Reid Hall.

Christiane Taubira greets Maryse Condé in the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc.

Christiane Taubira at Reid Hall.

Taubira followed with a moving conclusion to the conference. She recalled her first encounter with Condé as a student in Paris who had always associated literature with “dead authors” and “the posthumous transmission of knowledge.” Attending Professor Condé's classes was a revelation to her, as she discovered a young, elegant author who resembled her and who spoke to experiences similar to her own. Taubira, who was the driving force behind the French government’s official recognition of slavery as a crime against humanity with the passage of the loi Taubira in 2001, urged the audience to continue to explore Condé’s works that they might see the promise of “personal and collective emancipation” in her “inexhaustible and exacting portraits of humanity.”

"Je mourrai guadeloupéenne. Une Guadeloupéenne indépendantiste."

—

Maryse Condé remembered by former students and colleagues

“Maryse Condé's voice was simply unique. I can't think of any other writer in whose work the forces of history as they are lived in the bodies of individuals, and especially Black women, are rendered so present. Maryse the colleague was in my eyes very close to Maryse the writer: warm, curious, perceptive, ironic, combative. Her life, lived on three continents, was remarkable. After suffering adversity she plunged into the turmoil of decolonization in Africa. Then, in her 40s, the mother of four children, she channeled her personal and political experience, her research and her teaching, into her writing, becoming a star – and a game-changer – of francophone and world literature. Her life and writing have been an inspiration to many young scholars, students, writers – and will continue to be so. This is a painful loss for everyone who loved Maryse and her books, but above all for her husband and collaborator Richard Philcox, who made her voice as resonant in English as it is in French. My thoughts are with him and all of Maryse's loved ones.”

- Madeleine Dobie, Professor of French and Comparative Literature at Columbia University

“Maryse is and always has been there, at the very heart of the work I do – of the way I read and think and mother and teach – and it is hard to imagine a world without her in it. Except also somehow less hard, because of all she has given us to hold onto of love and rigor and wild indiscipline. I will miss her immensely.”

- Kaiama L. Glover, Ann Whitney Olin Professor of French and Africana Studies at Yale University

“I remember and treasure the electricity Maryse could create in a room. From a small dinner gathering at her home to a large lecture hall filled to capacity, she generated an inimitable mix of humor, intellectual rigor, and joy that I’ve never experienced anywhere else. Her warmth and curiosity brought so many into conversation, across the hierarchies of academe. Maryse changed the stakes in the fields of literary and cultural studies. She never let anyone get away with easy answers or grand claims about race, gender, culture, or power. In many ways we are still catching up with her.”

- Dawn Fulton, Professor of French Studies at Smith College