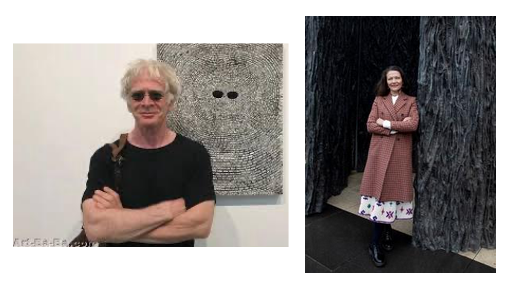

Behind the Honey Windows: Artist Kate Daudy in conversation with Matthew Armstrong (GS ‘84)

Matthew Armstrong (Columbia General Studies, ‘84) is the former curator of the PaineWebber and UBS art collections and is now a private curator and art advisor who lives and works in New York.

Kate Daudy is a British conceptual artist best known for her public interventions and large scale sculpture.

They spoke on December 17th 2023.

MATTHEW ARMSTRONG: What is the Honey Window?

KATE DAUDY: The Honey Window is a sculpture made from honey and a frame of wood from a fallen elm found in a municipal park in South London. I designed and worked out its construction with a superb English carpenter named James Trundle. Sandwiched within the frame are two sheets of glass between which 4 liters of honey has been poured, creating the effect of a stained-glass window. It casts a rich and beautiful golden light even when the sun’s not shining—like some beautiful spirit has paused while passing by.

MA: Does the disposition of the honey change?

KD: The effect changes with the light but the essential qualities of honey—not only its color but its semi-liquid state and its granular aspect is a constant. We expect that the honey is going to change continually over time, according to the temperature, the humidity and the light. Brunhilde Biebuyck, the Director of Columbia Global Centers | Paris, commissioned me to make the window. Originally it was to be ephemeral, for just one night as we wanted to demonstrate that art can be made from anything and didn’t have to be permanent.The result however was so beautiful—we all fell in love with it, so she kept it and commissioned me to make another one. So now Columbia has two permanent Honeywork installations at Reid Hall. They were originally intended for the outside of the newly restored Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc, but we moved them upstairs into a lovely light-filled corridor with a honey window at each end.

Image Carousel with 2 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: View of the two Honey Windows hanging in the glass veranda overlooking Reid Hall’s courtyard.

-

Slide 2: The first Honey Window installed outside the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc, commissioned for the first Nuit de l’Imagination on May 12, 2023.

View of the two Honey Windows hanging in the glass veranda overlooking Reid Hall’s courtyard.

The first Honey Window installed outside the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc, commissioned for the first Nuit de l’Imagination on May 12, 2023.

MA: Can one, in this corridor, detect that what one is seeing is not simply gilded light but in fact something in movement?

KD: Yes, you can see these little bubbles move. Slowly crystallizing and taking on different shades and hues. To me it reads as a measure of time and the influence of telluric forces on a natural substance. It is funny because, as I said, the original intention was to make something ephemeral but it is now permanently installed but the character of the piece—the governing idea—is mutability, is change. Permanently impermanent. There will be a significant transformation in the honey over the course of its life, which may be very long indeed as honey doesn’t “go off,” as such. If contained, it can last for a very long time. I have a friend who has eaten honey from inside a jar from an ancient Egyptian tomb and says it still was fresh.

Image Carousel with 5 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: Details: The Honey Windows hanging in the glass veranda.

-

Slide 2: Details: The Honey Windows hanging in the glass veranda.

-

Slide 3: Details: Honey crystallization.

-

Slide 4: Details: Honey crystallization.

-

Slide 5: Details: Honey crystallization.

Details: The Honey Windows hanging in the glass veranda.

Details: The Honey Windows hanging in the glass veranda.

Details: Honey crystallization.

Details: Honey crystallization.

Details: Honey crystallization.

MA: Fresh at four thousand years?

KD: Yes. Egyptians in ancient Egypt saw a parallel between honey and eternity. When babies died in ancient Egypt, they didn’t always mummify them. Often they would simply embalm them in honey.

MA: Where did your interest begin? What came first, the bees or the honey?

KD: Something that made a big impression on me as a child was a passage in Winnie the Pooh in which Pooh Bear, who has his paws full of honey, is floating by holding on to a balloon whilst being pursued by a swarm of bees, who burst his balloons and send him plummeting to the ground. Whenever I have traveled anywhere, I’ve always wanted to eat the local honey or get a little pot to bring home. When my children were small, we began to assemble a very large Honey Library with up to two hundred different varieties. I used to put pots of honey on the table with lots of spoons for us to express sensations and impressions through the medium of honey! I thought it was more interesting to learn from comparing similar things than overtly disparate things. The perception of subtle differences is essential in learning and the skill of using language to describe things which are non-verbal impressions is a wonderful challenge.

MA: Like in poetry, I suppose, language is used to create allusions which conjure responses that are beyond mere description.

KD: I’m very interested in language. I studied Chinese at university—I speak a few languages—and I am very interested in nuances of vocabulary and the spirit a language can express. An obvious example of this are the many different words the Inuit have for snow. Also, the way each person chooses to express themselves allows us to have a window into their soul, it is not just a question of education but articulation. The choices that people make in choosing their words are as if they are waving little flags about who they are. I was very interested when the children were little to get to know them better through this medium. If you say to someone, tell me about yourself, then it’s a bit constricting, whereas if you say, let’s all taste this honey, and each of us think of five words to describe an impression each honey makes on us, then you can get to know someone well, and how their mind works, and what they like to think about. Who they really are, which is what I’m very interested in. Honey also has these incredible visual characters, with some clear, some cloudy, and others can be as dark as black walnut or as pale as melted butter. My kids would describe the colors and different opacities in incredible ways.

MA: What’s the strangest or most far-flung honey that you have ever tasted?

KD: I was very keen to get some honey a very long time ago when we were in Madagascar—where honey is used as medicine—and doing so was very difficult. I went to a convent there because somebody told me that they had incredible honey. They did but wouldn’t sell it to me. But they did tell me of a man—a bee or honey man nearby who could fetch honey from a particular tree in a local village. I managed to track him down and he said he would love to help but I would have to give him a receptacle in which to put the honey. I had a water bottle and gave him that. He cut off the top and filled it with honey by gathering it with his bare hands from the honeycomb nestled within a trunk high up a tree. That great honey had such a beautiful glossy dark color and was thick and viscous, like reduced Coca-Cola. I had quite a time in my hotel room, trying to transfer it from this sawn-off water bottle into different receptacles so I could bring it back (illegally into the UK). Another time—through a swap—I got a lifetime supply of honey from Jerusalem. The honey from Jerusalem is some of the most delicious honey that you will ever taste. It’s almost transparent. It’s very pale, delicate, but unusually strong. And the idea that it comes from Jerusalem with its ancient past.

MA: The Land of Milk and Honey. What kind of honey is in the honey window?

KD: It's French and comes from an apiary in the Morvan region of southern Burgundy. We chose acacia honey for one of the windows and forest honey for the other. The idea of the honey window came from me wanting to use honey for a project that I’ve been involved with in Bolivia, where I’ve been commissioned to make biomorphic beehives. I’m going there in June to work with indigenous people in the cloud forest.

MA: Biomorphic beehives?

KD: Yes, based on the shapes that the honey made as it glooped into the window. It adhered to the surface of the glass in ways that were very unexpected. And it did these incredible loops and backwards dives, which was mesmerizing. It took hours to fill the honey window. When the people from the cloud forest asked me what shape I might like my beehives to be, I thought of these gloops and thought it would make the honey taste more delicious to be made into a kind of gloop shaped like a hive. I’m working on that now with drawings for the hives.

Image Carousel with 4 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: Details: The honey “gloops” as Daudy fills the window.

-

Slide 2: Details: The honey “gloops” as Daudy fills the window.

-

Slide 3: Details: The honey “gloops” as Daudy fills the window.

-

Slide 4: Details: The honey “gloops” as Daudy fills the window.

Details: The honey “gloops” as Daudy fills the window.

Details: The honey “gloops” as Daudy fills the window.

Details: The honey “gloops” as Daudy fills the window.

Details: The honey “gloops” as Daudy fills the window.

MA: Are these related to your upcoming exhibition in Madrid?

KD: The exhibition in Madrid is at the Circulo de Bellas Artes, it’s called Telling the Bees. It’ll be in autumn of next year. I’m very excited about that. There are no floating honey windows in that exhibition but I am planning a house made from honey. There have been a couple of technical issues which come from the sheer amount of honey within the structure’s windows. There are three or four kilos inside each window. We think if the space between the glass is made thinner, we’ll get an amazing effect from the honey and the structure won’t need to be so bulky. Matisse, you know, made some amazing drawings for the stained glass windows of the chapel of St. Paul de Vence—studies with honey colors and abstracted bee shapes. The windows were never realized but I was so happy to see that Matisse also loved bees and honey. He was interested, as I am, in the message that we can learn from man’s communication with bees and bees’ communication amongst themselves. Of working as one towards a common good. I think we’ve got a lot to learn from nature. Part of what we can learn from nature is humility and communicating with one another.

MA: And a show at the Sorbonne as well?

KD: I have a retrospective at the Sorbonne that’s running from October till November next year, which is a great honor.

MA: You have an enormous amount coming up next fall.

KD: Yes. I’ve also been commissioned to make a perfume, which is an interesting synaesthesia project. I wrote a poem and then worked with a nose to turn it into a fragrance. And that’s coming out in October, too.

MA: What is your perfume called?

KD: It had to be named after a location. I wanted it to be a location inside my spirit, which was the place inside your head when you get a good idea and it kind of flows. But they said that that wasn’t a real place… We called it Portobello Road, which is where I get most of that feeling from because it’s just outside my studio, and it smells of roses and tarmac.

MA: I’ve not yet seen the honey windows.

KD: Get yourself to Reid Hall which houses Columbia Global Centers | Paris and the Institute for Ideas and Imagination. They both host incredible public events, including the SNF Rendez-vous de l’Institut. It’s one of the most intellectually inspiring places I’ve ever been. It was an honor to give them something—that’s always a good way to leave things, with a gift.