Enrique Kirberg: A Chilean political exile at Columbia

Thanks to the efforts of Columbia faculty, Kirberg managed to escape the Pinochet regime and start over as a free man.

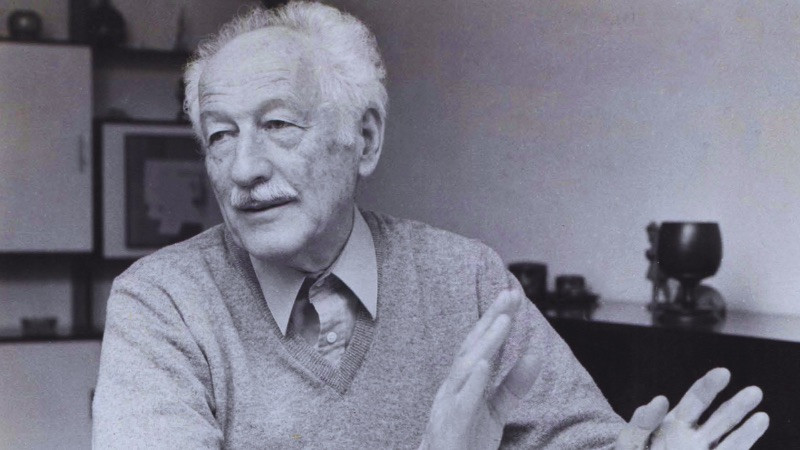

Underneath a bespectacled and austere demeanor, Enrique Kirberg lived a life in which he both bore witness to and took part in some of the most important developments of the second half of the 20th century. He was a strong advocate for the democratization of higher education in Chile, became the first democratically elected president of one of Chileʼs leading universities, survived two years of political imprisonment, and as an exile became an outspoken critic of the military regime that ruled over Chile for 17 years. This is the story of how a prominent Chilean academic managed to escape the Pinochet regime and get established in the United States for over a decade, following the concerted efforts of Columbia University faculty members who advocated in his name and secured him a teaching position that would allow him to be released from imprisonment and start over as a free man.

Early Years and Student Life

Enrique Kirberg was born to Jewish immigrants in Santiago on July 30, 1915 and raised in the port city of Valparaíso. At age 13 he entered the Escuela de Artes y Oficios (EAO), located in Santiago, where he lived as a boarding student for six years. Politically inclined from a young age, he joined the Communist Youth of Chile at 17. After being wrongly accused of organizing an art exhibit that was considered offensive by the schoolʼs authorities, and just one exam short of completing his studies, he was expelled and unable to graduate from EAO. By then, both of his parents had passed, and a maternal uncle helped him attain a job at the German electricity company AEG, where he worked repairing engines and other electric machinery. In 1935 he officially joined the Chilean Communist Party (PC). After becoming involved in protest movements, he was imprisoned and, along with other political and union leaders, sent to the town of Puerto Aysén in southern Chile. He was released three months later, but AEG did not accept him back, after which he worked for the PC in confidential activities. In 1942 he entered the newly founded Escuela de Ingenieros Industriales (EII), where he became student body president and from which he graduated as an electrical engineer in 1947.

In 1945 Kirberg was elected president of the first national organization of university students in technical fields, the Federación de Estudiantes Mineros e Industriales de Chile (FEMICH), sparking what would become a lifelong interest in the development of Chileʼs higher education system. Both Kirberg and the work of FEMICH were decisive in the 1952 foundation of the Universidad Técnica del Estado (UTE), of which he would eventually become president.

Academic and Political Life

After graduating, Kirberg established his own engineering company and became a teacher at EII and at Universidad de Chileʼs School of Architecture. For the next few years, his life was divided between academic activities, family and his growing participation in the PC. However, the latter would hit an impasse in 1948 due to the enactment of the Permanent Defense of Democracy Law, which banned the Communist Party in the country and called for its members to be persecuted and incarcerated. At the end of the 1950s, movements started arising within universities pushing for deep reforms, with students demanding more participation in decision-making processes and the election of their teachers and authorities. Kirberg sympathized with the demands of the movement that would sweep through the country in the following decade. In his own words, the changes were necessary to put universities “in direct contact and at the service of the public, to make them more humanistic.” In the next years, Kirberg would take an increasingly prominent role within the Communist Party. In 1966 he was appointed head of the PCʼs National University Commission, which oriented the work of militants inside Chilean universities. A year later the student movement within UTE, backed by numerous professors and university staff, achieved an important goal: President Eduardo Frei Montalva approved the creation of a reform committee –integrated by academics and students– to draft a new organic statute for the institution. In Kirbergʼs words: “Inside UTE the reformist movement was unstoppable. At that point there was considerable support from the teaching staff for student demands, although the most serious proposals for structural and functional reforms came from the student body.” Horacio Aravena, who had been university president for almost a decade, resigned in April 1968 and democratic elections were called for the first time at UTE. Four months later and after an extensive campaign that took him to several UTE campuses throughout the country, Kirberg became the first democratically elected president of the university after attaining a resounding 75% of faculty and student votes.

President Kirberg

At the time of his election, Kirberg had been a faculty member for two decades and therefore was well known within the university given his participation in its foundation during his years as a student at the former EII. Although there were only a few members of the PC among the faculty, the Communist Youth was strong among the student body – they presided over the student union– which according to Kirberg, was key in securing his triumph. He was re-elected in 1969 and again in 1972, the latter for a four-year term that was slated to last until 1976. In Kirbergʼs view, “the simple joining of schools had not made the UTE a university. There was no research or university outreach. In my opinion, outreach was the essential ingredient to make a more humanistic university.” In consequence, under his leadership, UTE continued its path towards democratization and modernization, which included the establishment of an inclusive co-government (between authorities, faculty, staff, and students), pushing for university autonomy, academic freedom, and outreach activities through an open-door policy that aimed to open up the university to students and non-students alike throughout the country. But his most notable achievement was the development of what came to be known as the “Kirberg Plan,” an attempt to bring together all Chilean universities to develop institutes and offer technical majors, especially to workers, in order to provide them with better career options.

Another major concern of Kirberg was to promote UTE as a reputable institution on an international level. With this in mind, he hired Jaime Michelow, Chileʼs first PhD in Mathematics, and Herbert Clemens, who at the time worked as an assistant professor of Mathematics at Columbia University, to create the countryʼs first postgraduate program in the field: the Licenciatura Académica Matemática (LAM), a rigorous curriculum, partly funded by the Ford Foundation, which aimed to form the next generation of Chilean mathematicians. During the northern hemisphere summer recesses of 1972 and 1973, Clemens traveled to UTE to teach and help oversee the program. In Clemensʼ words, Kirberg supported his work “one hundred per cent, despite political suspicion of Americans in Chile.”

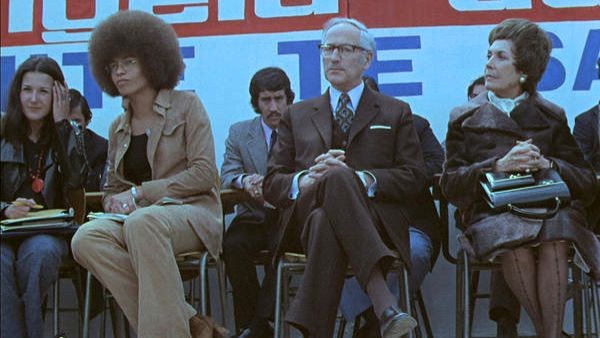

Kirbergʼs efforts towards internationalization of the university led to very prominent figures visiting UTE during the early 1970s. After meeting him during a trip to the United States the prior year, two-time Nobel laureate Linus Pauling visited UTE in 1970 to conduct a series of seminars and conferences for students and academic authorities. Two years later, political activist, university professor, and US Communist Party member, Angela Davis, visited Chile to attend the 1972 International Congress for Peace taking place in the country. The African American feminist icon landed in Santiago in October in a demonstration of support for socialist President Salvador Allende, who was facing a particularly difficult period of his troubled time in power. After the end of her 16-month long political imprisonment, Davis did an international tour that took her to various socialist countries, including Cuba, the USSR, and the German Democratic Republic. Part of her Chilean agenda included a visit to UTE, where she gave a conference to students, authorities and then First Lady Hortensia Bussi. While in the country, Davis condemned what she said was a US campaign of terror on the Allende administration and committed to defend Chilean interests in her country.

Coup and imprisonment

The morning of September 11, 1973, President Allende was set to speak at UTE to inaugurate the Campaña por la Vida (Campaign for Life), a pacifist attempt to decompress the tense social and political situation. However, the day played out differently: the university radio station was attacked, and its communications were shut down. When, looking through the windows, students saw the bombing of the presidential palace and heard what would be Allendeʼs last speech on the radio, they knew a coup was underway. Over a thousand students barricaded at the universityʼs central building in support of the government. By the following morning, all of them had been arrested; many of them would turn up dead in the coming days. A military delegation sent to the school was met by Kirberg at the main entrance, where he attempted to negotiate a peaceful exit. Kirberg would later recount how he and student body president Osiel Núñez were held at gunpoint against a wall, anticipating being executed. The following morning, all students were transported to Estadio Chile, a stadium rapidly turned into a political prison, where over 5,000 prisoners were tortured and/or executed, including legendary folk singer and theater director at UTE, Víctor Jara, a close acquaintance of Kirbergʼs. On September 15 Kirberg was moved to Isla Dawson, an island located in Tierra del Fuego, an archipelago at the southernmost tip of the South American continent. Along with other prominent members of the PC and collaborators of the Allende administration, such as Orlando Letelier, former ambassador to the United States and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Interior and Defense, and Sergio Bitar, who had been Minister of Mining, Kirberg spent nine months in this location, where he was subject to forced labor, torture, and surveillance, under a constant fear of death.

Campaign for Kirbergʼs Release and Arrival at Columbia

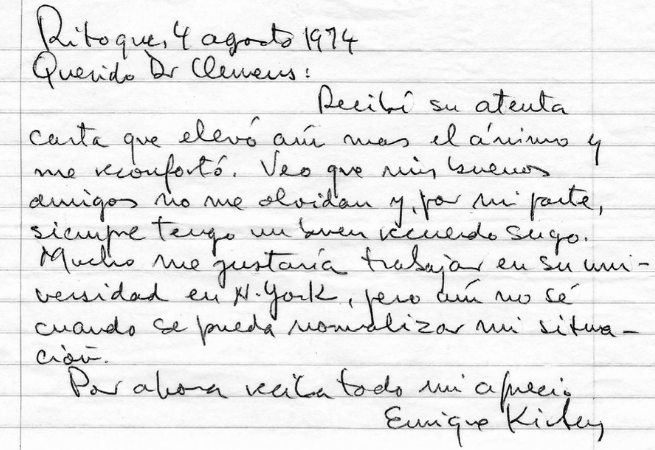

In May 1974, Kirberg was moved from Isla Dawson to Ritoque, in central Chile, where living conditions were slightly better and access to the outside world was more available. In November that same year, he was relocated to Capuchinos, a prison located in Santiago, where he was reunited with several UTE students.

Around this time, the US academic community started organizing to secure Kirberg a job in the country, hoping that this would be his way out of Chile. Over 20 declassified documents from the United States Department of State as well as several articles published in the Columbia Spectator student newspaper, evidence both the international campaign put in motion to secure Kirbergʼs liberation and the Chilean governmentʼs efforts to delay it. As it can be read in an October 1974 cable, when Kirberg was still at Isla Dawson, Chilean authorities charged him for tax evasion in relation to an alleged bank account in US dollars that Kirberg had during the Allende government. Even though the charge was appealed, the Chilean court did not dismiss the case, as it stated in a January 1975 document.

At the same time, Orlando Letelier, Kirbergʼs former inmate at Isla Dawson and Ritoque, had reached out to Herbert Clemens at Columbia Universityʼs Mathematics Department, urging him to find a position for Kirberg, as he anticipated it was likely that the Chilean authorities would release him if he had an offer to work in another country. Thus, in May 1975, Clemens initiated a campaign which resulted in 57 academics from the universities of Harvard, Massachusetts, Brandeis, Columbia and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, sending a telegram to the Organization of American Statesʼ (OAS) Human Rights Commission expressing their concerns over reported human rights violations in Chile, specifically within the academic community. In said message they addressed Kirbergʼs situation, who by then had been imprisoned for 19 months with no trial, stating: “He is being held under inhumane conditions--his basic human and legal rights systematically ignored.”

The following month, Clemens visited the Chilean ambassador to the United States, Manuel Trucco, hoping to expedite Kirbergʼs liberation, after which he approached the Department of State, as it can be read in a document from June 4: “Today Columbia University professor Herbert Clemens visited department to say he had just talked with ambassador Trucco for 45 minutes. Clemens said Trucco called Schweitzer [Miguel Schweitzer, Chilean ambassador to the United Nations] in Santiago to discuss case and then told Clemens that Kirbergʼs <> would soon be ended, and he could then be expelled on one way passport if he had some destination.”

The same document states that Columbia University President William McGill was already requesting assistance in facilitating Kirbergʼs acceptance of a senior research associateship from September 1975 through May 1976. A following cable, dated June 18, indicates that Chilean Minister of Interior, César Benavides, was aware of the position Kirberg had been offered at Columbia and of the international efforts being made to secure his release. The document also reveals that Trucco believed that because Kirberg was a member of the Communist Party, he would not be eligible for a permanent entry to the United States under a parole program, “but could be admitted for temporary academic employment.”

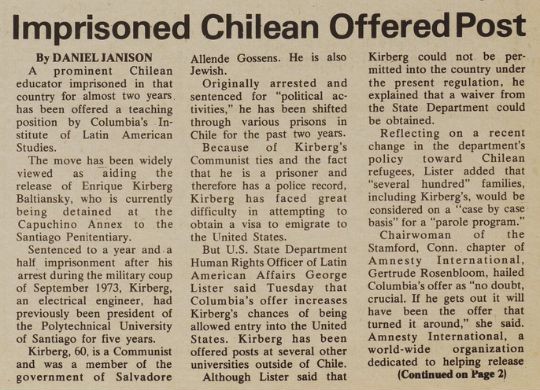

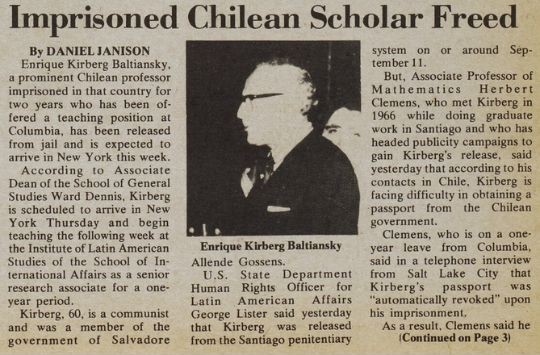

The campaign for Kirbergʼs release was covered in depth by the Columbia Spectator student newspaper. In several articles published during 1975, the efforts of Clemens, University President William McGill, Associate Dean of the School of General Studies, Ward Dennis, as well as those of Gertrude Rosenblum, Chairwoman of the Stamford, Connecticut chapter of Amnesty International, and of Human Rights Officer of Latin American Affairs at the US Department of State, George Lister, are evidenced. In an article from June that year, which detailed Columbiaʼs offering of a teaching position to Kirberg, Rosenblum stated that “if he gets out it will have been the offer that turned it around.”

Rosenblum also acknowledged Clemensʼ personal involvement in the case and his role in gathering support. By then, in addition to the actions taken by the aforementioned academics from east coast universities, over ninety amnesty groups in the United States had also appealed in favor of Kirberg towards the Chilean Junta.

Meanwhile, as expected, Kirberg had been charged for tax evasion and sentenced to an additional 18 months in prison. However, by mid-1975 the sentence had not been confirmed. According to the aforementioned June 18 cable, after speaking to the Minister of Interior, Kirbergʼs defense lawyer was confident that the Chilean government would withdraw the charges. A July 10, 1975, document states that Kirbergʼs wife had visited him in jail the previous day, where he had told her he feared the government “was attempting to pile up fines against him which he cannot pay, and thus have <> to continue to hold him.” In the comments section of the cable, it reads that Kirbergʼs concerns were understandable given his long imprisonment, and that “it is not inconceivable that GOC [Government of Chile] wants to damage Kirbergʼs reputation further before releasing him,” although it also records that this “conflicts with information from Kirbergʼs lawyer who has been discussing case with mininterior [Ministry of Interior] and who has felt up to now that GOC planned to release Kirberg soon.”

A month later, one of Kirbergʼs daughters phoned the US Embassy in Chile after visiting her father in prison. During the call, as it is stated in a document from August 25, she mentioned that he seemed to be in good health and in much better spirits than the previous month. It is also noted that, by then, Kirbergʼs family knew that the tax charges would be dismissed in the following days and that they expected him to be released. Two years to the day from his initial imprisonment, Enrique Kirberg was released on September 11, 1975. He was to spend 12 days in freedom in Chile before traveling to New York to begin his teaching position at Columbiaʼs Institute of Latin American Studies (ILAS) in affiliation with the School of International Affairs.

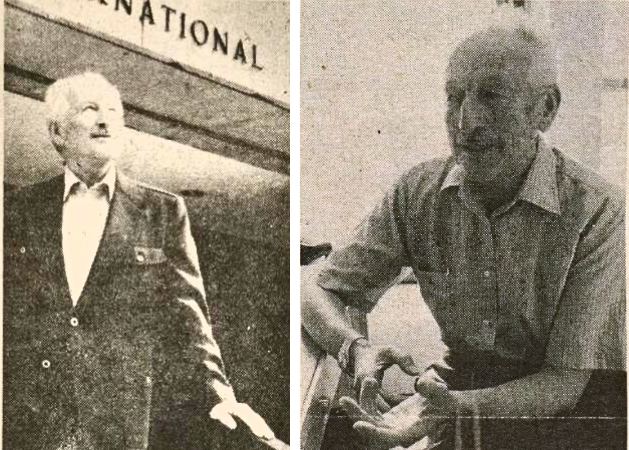

When asked about his impressions of those first days of freedom in Chile, Kirberg stated: “I have the feeling of having been in a dark country, in a heavy night. You couldn’t even read the papers because they lied about everything. Every piece of news was censored.” Before leaving the country, he had to visit the US Consul in Santiago, who informed him that US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, had authorized him to enter the country in spite of his affiliation with the Communist Party and that he had been convicted for tax evasion. “The consul had all the documentation regarding my case. It was clear to him that my process had been fabricated with the sole purpose of convicting me and thus justifying the dictatorshipʼs actions in the public opinion, so he granted me a visa,” Kirberg recalled. It was only then that Kirberg could leave the country thanks to a grant provided by the Ford Foundation that covered his airfare. Upon his arrival in the US, Kirberg was greeted by the National Coordinating Center in Solidarity with Chile at a New York airport.

Immediately after, he visited Boston, where he met former inmate from Isla Dawson, Sergio Bitar. Around 35 people attended a welcoming reception held in his honor at Harvard University, with the attendance of Amnesty International representatives. Among them was Gertrude Rosenblum who told the Columbia Spectator Kirberg was thrilled to be there and aware of the international support he had received in order to attain his freedom. Shortly after, he returned to New York to start his work at ILAS, where he was greeted by director Doug Chalmers. The University helped Kirberg rent a small apartment and get settled in the city. While he waited for the arrival of his wife Inés, who landed in New York two months after, he, along with Chalmers, worked closely to devise a curriculum for the seminars he was to teach.

Kirbergʼs first academic activity at Columbia was a brown bag lunch lecture entitled “El Chile de Hoy” (Chile Today), attended by over 100 professors and students. He then taught a class called “Historia Contemporánea de Chile” (Chilean Contemporary History), which covered 1879-1970s. He also gave a lecture at Teachers College on the role of universities in economic development, which he would repeat three times throughout the year. In addition, he started writing a book entitled “Los Nuevos Profesionales” (The New Professionals), in which he narrated the reform process at UTE, and the program that focused on providing university education to workers. During the spring of 1976, he met up with Herbert Clemens, who by then was a professor at the University of Utah.

At the end of the 1975-76 academic year, Chalmers informed Kirberg that ILAS lacked funding to pay for his salary in the upcoming semesters. In response, Kirberg then applied for and was granted funding from the Ford Foundation. In the following years he would receive grants from the foundations Twinbrook, Rubin, and Kaplan, as well as from the Fund for Tomorrow, which allowed him to remain at Columbia.

Additionally, every year, the University maintained that he was a faculty member before Immigration Services so as to secure his stay in the country. Immigration policies became stricter during the Ronald Reagan administration, with authorities demanding the school provide proof of his work with the institute to which he was affiliated. University authorities praised Kirbergʼs contributions, stating his presence was required at least for the following years.

Apart from his work at ILAS, during his 11 years at Columbia, Kirberg gave several on-campus conferences and lectures on varied topics, including “Nitrate Mines and Worker Organizations” (March 1976); “The Popular Front,” including repercussions of World War II and the significance of the copper corporations in Chile (March 1976); he spoke about the difficulties of the Allende administration, the 1973 coup, the Military Junta ruling over Chile (April 1976), and “From Frei to Allende: The Non-Violent Way. Characteristics of the Allende Government” (April 1976). In addition to his work at Columbia, he taught mathematics courses at Eugenio María de Hostos Community College in the Bronx, and at Essex Community College in New Jersey.

Political Activities

Along with his academic work, during his years in exile Kirberg played an active role in the solidarity movement with Chile, which included unions, academic associations, churches, synagogues, councils, and other civic organizations that aimed to denounce and create awareness about the countryʼs situation under the Pinochet dictatorship. He also helped to raise funds to support victims of the dictatorship and their families in Chile. “During my 11 years in the United States, I must have given some 80 lectures throughout the country. I collaborated with the National Coordinating Center in Solidarity with Chile, based in New York…We visited universities in Oregon, California, Illinois, and Massachusetts. They covered the expenses of our accommodation and tickets. What the universities paid us –which were significant amounts of money– went to the solidarity movement with Chile,” recalled Kirberg.

These activities were also led by prominent figures of the Chilean opposition such as Orlando Letelier, as well as Cristián Orrego, Juan Gabriel Valdés, and Giorgio Solimano (a pediatrician and fellow exile who had worked at the Ministry of Health under Allende and who at the time was also a faculty member at Columbia and close friend of Kirberg). Along with Kirberg, they worked closely with various human rights and solidarity organizations, such as Amnesty International, the Columbia Committee for Human Rights in Chile (CCHRC), the Chile Solidarity Center, and Americaʼs Watch. Their work consisted in organizing rallies, conferences, gathering humanitarian support, and using diplomacy to put pressure on Pinochetʼs regime. Through the Chile Solidarity Center, among other activities they organized visits from Chilean personalities. Through one of these, Jaime Castillo Velasco, Máximo Pacheco Gómez, and Gonzalo Taborga, who were prominent members of the Chilean Human Rights Commission, could attend the United Nations General Assembly, where they raised the issue of the human rights violations in Chile. “All of our activities were centered around the fight against the dictatorship and the freedom of our country,” assured Kirberg when remembering those days.

During March 1978, Kirberg organized two activities aimed at the academic community. On March 1, along with Solimano and Claudio Grossman –former president of the Law Student Federation of Chile, who at the time was working at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands– visited Harvard University, where they met with students, as well as President Derek Bok and Henry Rosovsky, Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. During the encounter, the Chileans talked about academic repression under Pinochet and asked the Harvard community for support in using all available resources to help find the 2,500 detenidos desaparecidos who had been subject of forced disappearances since the 1973 coup.

A similar activity took place two days later at Columbiaʼs Teachers College. The symposium, entitled “The Chilean University: Education and Political Repression in Chile,” was organized along with the CCHRC and featured Kirberg, Grossman, and Roberto Belmar, former Chilean National Health Service worker, then working at Yeshiva University in New York. During the encounter, Kirberg denounced the USʼ role in destabilizing the Allende government and in the coup itself. He noted that since 1973 there had been a $500 million increase in loans and credit to the Chilean government, which, among many other offenses, was rolling back several of the educational reforms he had implemented at UTE. Belmar, on the other hand, was critical of the privatization of public health in the country. “The Junta has adopted [economist Milton] Friedmanʼs view that medicine is a marketable commodity, not a right,” he pointed out. The Chileans also urged the audience to contact their legislators to pressure the Chilean authorities into revealing the whereabouts of those who had been forcefully disappeared.

Other actions of solidarity included organizing demonstrations and cultural activities that over the years were attended by relevant Chilean performers like Patricio Manns, Inti Illimani, Quilapayún, and members of the Parra family. Kirberg recalled the support received by those that were committed to the Chilean cause, highlighting the role of Susan Borenstein, coordinator of the National Coordinating Center in Solidarity with Chile, and of journalist Samuel Chavkin, author of “The Murder of Chile” and “Storm over Chile”, two books that openly denounced the human rights violations. Remembering his years in New York and his political activism along with Kirberg, Giorgio Solimano adds two people to the list of remarkable activists: Aryeh Neier, co-founder of Human Rights Watch, and Cynthia Brown, associate director of Americaʼs Watch, who from 1983 took yearly trips to Chile to monitor the human rights situation in the country.

According to Solimano, Columbia University supported the activities he and Kirberg carried out while working in the United States. “We could perform our political actions without any conflicts with our academic work. There were no intentions to limit Enriqueʼs activities because of his affiliation with the Communist Party,” he says, adding that Columbia authorities valued them for their achievements during the Unidad Popular government. “They acknowledged what we had been through in Chile. They respected us and provided the conditions for us to carry out activities against the dictatorship, which at the time were expensive, like using computers and making long distance phone calls.”

These activities were by no means safe. As the main international voice of the Chilean opposition to the dictatorship, Orlando Letelier put significant pressure on the US Congress and European governments to halt financial aid to Pinochetʼs regime. In retaliation for his public actions, in June 1976, Pinochet responded by stripping him of his Chilean nationality. Three months later, Letelier was assassinated in Washington DC, in a September 1976 car bomb operation orchestrated by the dictatorshipʼs secret police, the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA). In a 1978 interview with the Columbia Spectator newspaper, Kirberg was asked if, given his public opposition and criticism of Chileʼs military Junta, he was afraid of meeting the same fate as Letelier. He responded: “Yes, I did fear for my own life after the assassination of my friend Orlando Letelier. Later, I arrived at the conclusion that the Junta would try to avoid further judicial conflicts with the United States. That idea has made me stop worrying.”

Life in New York and Longing for Chile

Although he was forced to live outside his home country, Kirberg was thankful for his life in New York. When asked about his initial feelings in exile, he claimed: “I would say freedom rather than exile. I walked the streets of New York, through Broadway, with a feeling of joy.” He was also emphatic about expressing his appreciation towards Columbia University: “After two years spent in concentration camps in Chile, my appointment here at Columbia was decisive in obtaining my freedom and permission for me to leave the country.” However, perhaps his idealistic nature had led him to expect more political compromise within the school, since although he witnessed student activities, he felt these were sporadic and temporary, with only a minority of students taking part in them, and that they were not monitored by the official student organizations. He also noticed that while the faculty was very active in organizing conferences and lectures around political subjects and human rights issues, these discussions tended to be mostly analytical, rarely leading to concrete actions towards solving these problems. But none of this prevented him from expressing his gratitude towards the university: “I am especially grateful to President William McGill and Dean Ward Dennis, and to the large number of professors who expressed their solidarity and contributed to my appointment and, therefore to my freedom.”

In Solimanoʼs view, despite the situation, his friend enjoyed a pleasant and comfortable life in the US. “We lived two blocks away from each other through the Columbia campus. I lived towards the river, and he lived towards the East Side. We were very close and we shared an ideological affinity. I have never been a member of the Communist Party, but while living in the United States we were fighting for the same goal,” he says. While Kirberg lived with his wife, Solimano, who is significantly younger, was still single and frequently met with the Kirbergs socially. They shared an interest in cultural activities, attended concerts, exhibits, and relished discovering different ethnic restaurants.

“We enjoyed trying Cuban and Dominican food and going to stores that sold foreign products. Columbia also offered a wide range of cultural and sport activities,” he recalls. But above all, “Enrique was a big reader.” Looking back to those years, Solimano defines his friend as a smart, affable person, with ideological clarity “which earned him the respect of the people who interacted with him. It was important for him to be there [in New York], do his job, and start writing his book [Los Nuevos Profesionales].”

In the aforementioned September 1978 interview with the Columbia Spectator, Kirbergʼs eternal optimism is revealed. He was confident that he would be able to return to Chile shortly and work in his profession in his own country since, as he believed, the dictatorship would not last much more. In his view, Chileans would not tolerate for much longer being deprived of democratic freedom, participation, individual and union rights, or the ability to elect their own authorities. He praised the resistance of his people against the dictatorship and held faith that they would reject the imposition of a new constitution, which was already underway: “All this makes me think that the Junta will not last for long… I think that we will soon see changes that will permit the beginning of a democratic reconstruction of the country and the return of the exiled people,” he predicted.

But he was wrong. The “heavy night” that he perceived had fallen over Chile when he was released from prison in 1975 would last for yet another 15 years. During his 11 years at Columbia, he visited his country once, in 1980. Technically, when Kirberg first left Chile, he had not been exiled. As such, he could legally enter, but he avoided this for several years because he knew it would be risky. His 1980 trip lasted three weeks. There were no receptions or public gatherings since he had been warned that he might be kidnapped. Moreover, a letter addressed to Kirberg arrived at the house of one of his daughters, warning him that he would meet the same fate as his late friend Orlando Letelier.

A second letter addressed to his daughter threatened her and her family if she “continued sheltering a communist.” A few months after his return to the US, his wife –who was in Chile at the time– let him know that she had been informed the dictatorship had issued a decree forbidding him from re-entering the country. “It was a huge shock. I felt like the monster [the regime] had stepped on me. I was by myself in the US and was depressed for a few days,” he said. Although in 1981 he had to visit the Chilean consulate where the infamous letter “L” was stamped in his passport, he said that “people at Columbia University were very sensitive about this and expressed their solidarity with me. From then on, I truly felt like I was in forced exile.”

His years at Columbia ended abruptly in 1986. He had traveled to Europe to visit one of his daughters but was denied a visa to return to the US. The alleged reason was his status as a “visiting” faculty member, a category that could only be held for up to five years, whereas he had been in the country for over a decade. He was then forced to accept a position he had been offered at Universidad de la República in Montevideo, Uruguay. Thanks to diplomatic arrangements made by Chilean friends and fellow academics in New York, the US consulate in Frankfurt granted him a visa to enter the country. He only returned to arrange his belongings before relocating in Uruguay. When consulted on why he never sought political asylum or permanent residency during his 11 years in the United States, Kirberg claimed that he always intended to return to Chile and that because he was known communist, he never initiated the legal procedures to get a Green Card because he thought the possibility of permanent residency was virtually impossible.

By 1987 he had been granted permission to re-enter his home country again, so he traveled to Chile from Uruguay. During that visit, he met with Chilean journalist Mónica González, who inquired about how he felt about his long stay in the US. “I made the most of my time there. I believe that today I would be a better President with everything I learned from North American universities, which complement the good things that Latin American universities have,” he responded. “I learned many things, my horizons widened, and I was able to enjoy the solidarity of the true American people.”

Return to Chile and Final Years

After two years in Uruguay, Kirberg finally returned to Chile in May 1989. Seven months prior, Pinochet had been defeated in a referendum over his rule, inaugurating a period of transition to democracy. Presidential and congressional elections were held for the first time in 19 years in December 1989, with Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin winning the presidency. On March 11, 1990, Pinochet left power and democracy was reinstated in Chile.

Kirberg described his first months back in the country as almost euphoric, filled with receptions, parties, and reunions, but once the party –which according to him lasted around two months– was over, the returned exiles faced the hard reality of having no job and no financial security. In consequence, he became very critical of the returneesʼ difficulties in rejoining the work force, and he was disappointed that the Chilean transition was to a great extent limited by the terms the dictatorship had defined. In spite of these views, he supported the transitional process, valuing the triumph of democracy, the end of the dictatorship, and the return of the respect for human rights. He was always optimistic about Chileʼs future, but he warned: “No one is going to grant us democracy. We must build it, demand it, share it, take care of it, and defend it.”

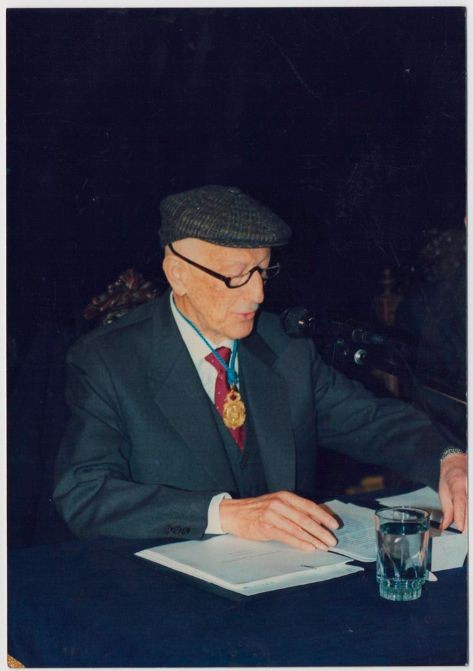

When Luis Cifuentes conducted the series of interviews with Kirberg that resulted in the publication of a book on the latterʼs life, Kirberg was 76 years old and had great plans ahead. He had just been awarded an honorary doctorate degree at Universidad de Santiago de Chile (of which UTE was the predecessor) and was offered a position to work with students who were writing their theses.

He had also joined Universidad de Valparaíso, where he was put in charge of a cultural program. He wanted to keep writing and had in mind a new essay on university education and was looking forward to traveling with his wife Inés. Even though by then he had been diagnosed with cancer, he was determined to get healthy and to see his dreams fulfilled: “I dream of the society of the future. A society with no misery or injustice, a society in which children are happy, so that they can later become normal citizens. A society in which the problems of environmental pollution are solved, in which there are no endangered species. I dream that humankind will make this planet one where they can live in peace and joy.”

Enrique Kirberg passed away on April 23, 1992, and although he did not live to see all of his plans and hopes fulfilled, he was a man that lived life to the fullest. A man that was both a witness to and a leading actor in the tumultuous times of Chileʼs 20th century, who is remembered as a tireless fighter for equality and dignity, as a fundamental actor in the democratization of Chilean education, but above all, as an eternal optimist. As he once said: “I do not have resentments nor am I encouraged by revenge. Maybe thatʼs a flaw of mine, but I donʼt hold grudges. I believe that in the end justice prevails, that truth, and happiness will triumph… one day.”

The full version of this text was published in the book “Columbia University and Chile. Over 100 Years of History,” available here.